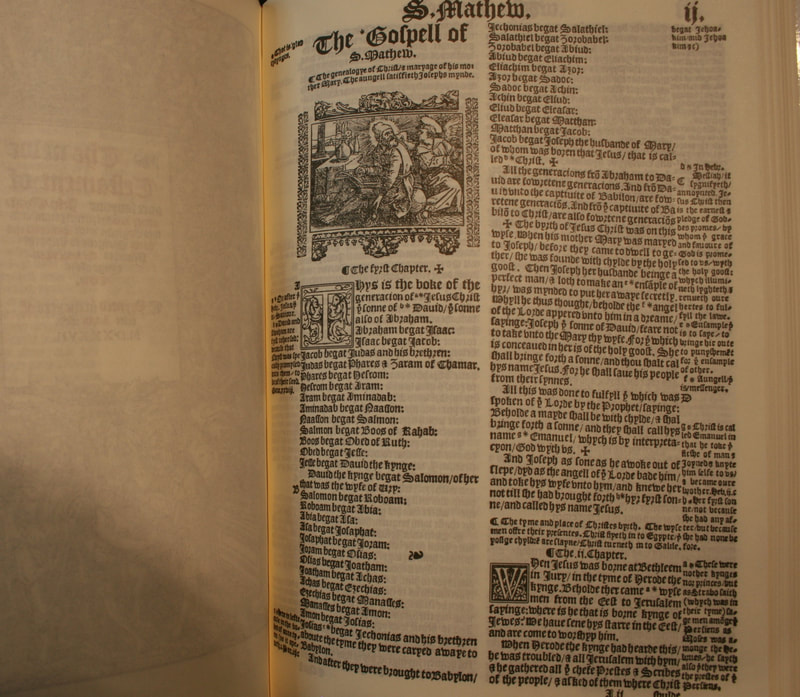

1537 Matthews Bible

by John Rodgers

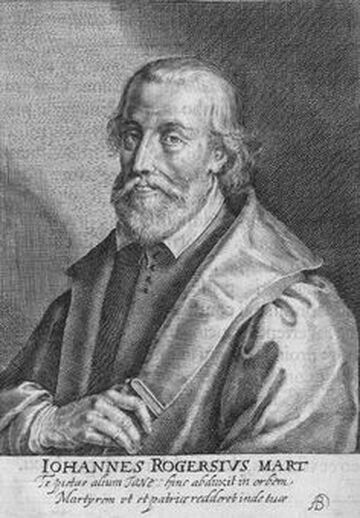

ohn Rogers, born 1500 in Deritend, England, became another Cambridge student and was influenced by Reformers Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer. In 1534, he came to Antwerp by the Merchant Adventurers and became the chaplain of the English factory at Antwerp. William Tyndale, also being in Antwerp at this time, came to meet Rogers, and became good friends. As discussed previously in the account of Tyndale, Rogers continued Tyndale’s life-long work and dream of one day publishing the entire Bible in English.

John Rogers 1500-1555

John Rogers 1500-1555

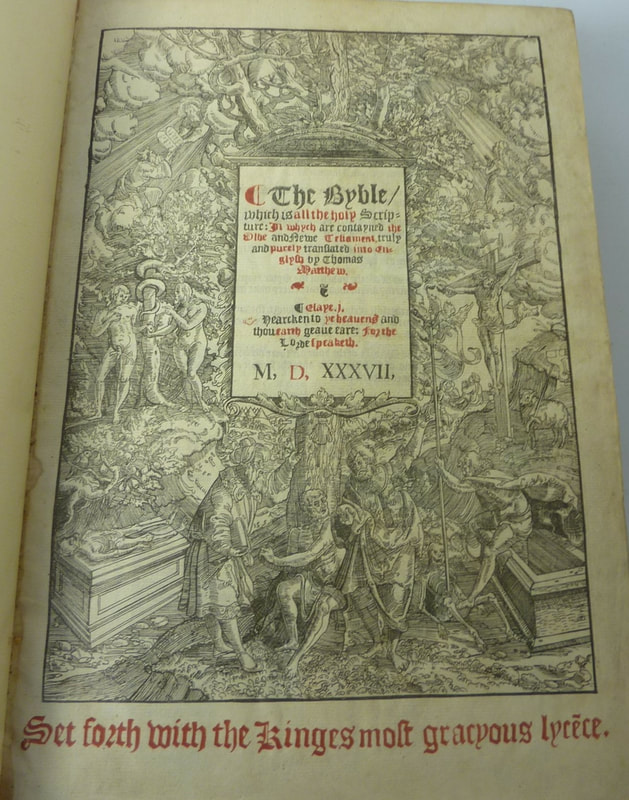

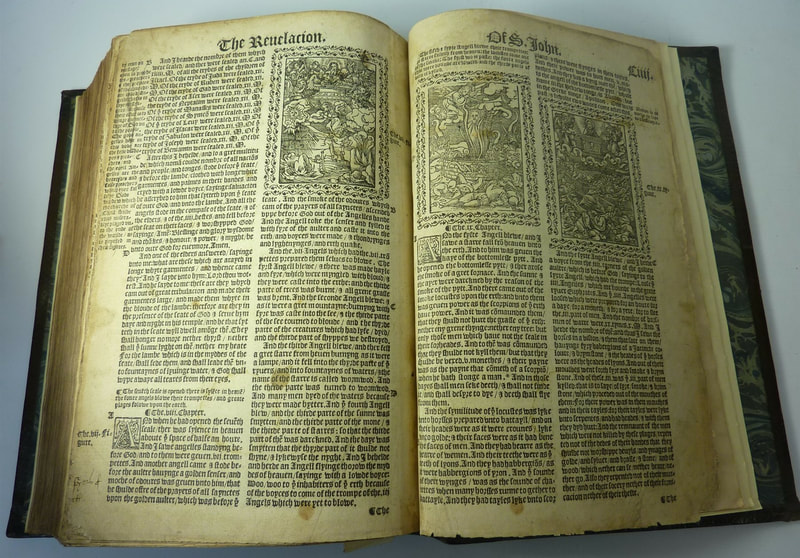

At the arrest of Tyndale in 1535, Rogers was safely guarding the manuscripts of Tyndale’s latest translations, which included Joshua thru 2Chronicles and Jonah. Shortly after the conviction and death of Tyndale in 1536, Rogers, one year later, would publish the entire Bible in English under the pseudonym, “Thomas Matthew”. It is suggested he did this to protect his name from the persecution Tyndale had a year previous been afflicted.

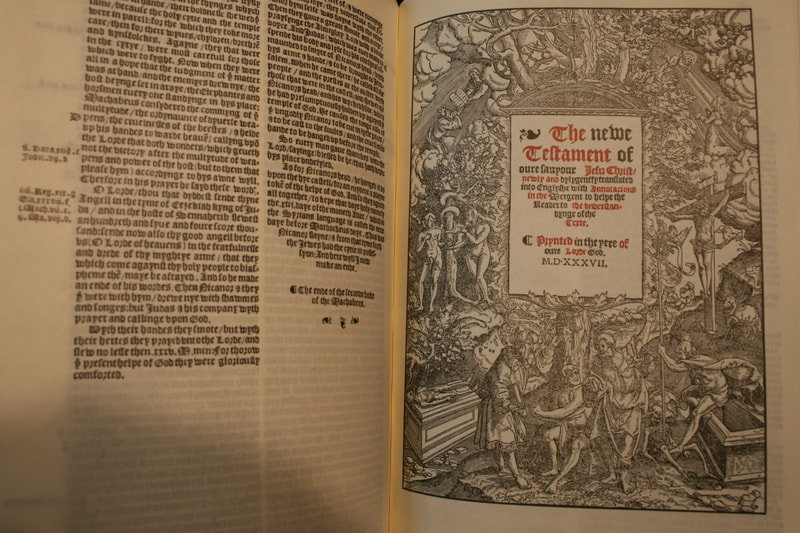

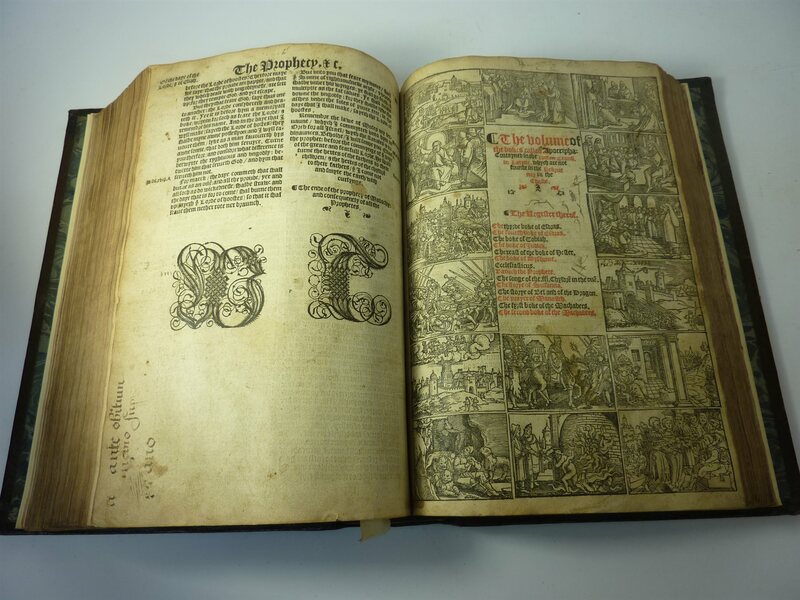

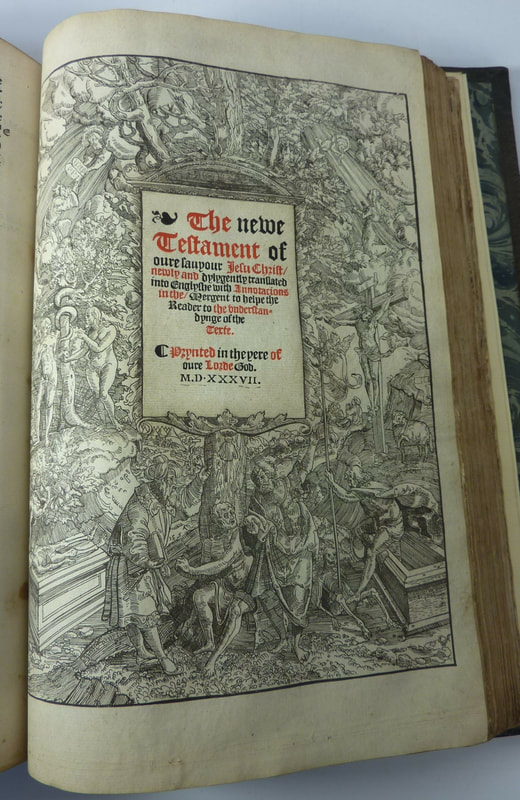

Unlike the Coverdale Bible, John Rogers, being partial to William Tyndale’s work, chose to use Tyndale’s translation where he could, and he even included the controversial marginal notes and prologues, particularly the prologue to the epistle of Romans. However, he chose to use Coverdale’s translations for the remainder of the Bible in which Tyndale had not translated. Thus, the Matthew’s Bible is the most complete Tyndale translation. Being comprised of Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament, the Old Testament books from Genesis to 2Chronicles, and Jonah. This would also explain the urgent pace in which this work was put together. John Rogers compiled the Bible as an editor would, rather than a translator, thus the Matthew’s Bible was published less than a year after the death of William Tyndale.

Roger’s work was done in secret, therefore we do not have much information on its progress, however, we do know that the printing was accomplished in Antwerp, at the hand of printers Richard Grafton and Edward Whitechurch. It is unknown exactly how Grafton become the appointed printer for this Bible. My conjecture is Grafton was a business man in Antwerp and probably an acquaintance of John Rogers. Rogers, having in his possession of the only manuscripts of Tyndale, would not have trusted the printing of this Bible to someone he did not know or trust. It had to be an ally to the Reformation and a supporter of the new movement.

Another reason Grafton was chosen as the printer of this Bible, was his connections with Archbishop Cranmer and vice-regent Cromwell. Since the production of the Coverdale Bible just two years prior, it had opened the door to the acceptance of the English Bible. Although hated by the Romish party, the king was growing in favor toward the notion with the help of Cranmer and Cromwell at his side. To obtain the official license of the king, Grafton gave a preliminary copy to Archbishop Cranmer. Cranmer had a love for the Scriptures and an extreme zeal for the English Bible. Upon receiving the Bible from Grafton, Cranmer said it was a “delightful surprise”, and supported the production of this English edition fully. On August 5th, 1537, Cranmer wrote a letter to Cromwell:

Unlike the Coverdale Bible, John Rogers, being partial to William Tyndale’s work, chose to use Tyndale’s translation where he could, and he even included the controversial marginal notes and prologues, particularly the prologue to the epistle of Romans. However, he chose to use Coverdale’s translations for the remainder of the Bible in which Tyndale had not translated. Thus, the Matthew’s Bible is the most complete Tyndale translation. Being comprised of Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament, the Old Testament books from Genesis to 2Chronicles, and Jonah. This would also explain the urgent pace in which this work was put together. John Rogers compiled the Bible as an editor would, rather than a translator, thus the Matthew’s Bible was published less than a year after the death of William Tyndale.

Roger’s work was done in secret, therefore we do not have much information on its progress, however, we do know that the printing was accomplished in Antwerp, at the hand of printers Richard Grafton and Edward Whitechurch. It is unknown exactly how Grafton become the appointed printer for this Bible. My conjecture is Grafton was a business man in Antwerp and probably an acquaintance of John Rogers. Rogers, having in his possession of the only manuscripts of Tyndale, would not have trusted the printing of this Bible to someone he did not know or trust. It had to be an ally to the Reformation and a supporter of the new movement.

Another reason Grafton was chosen as the printer of this Bible, was his connections with Archbishop Cranmer and vice-regent Cromwell. Since the production of the Coverdale Bible just two years prior, it had opened the door to the acceptance of the English Bible. Although hated by the Romish party, the king was growing in favor toward the notion with the help of Cranmer and Cromwell at his side. To obtain the official license of the king, Grafton gave a preliminary copy to Archbishop Cranmer. Cranmer had a love for the Scriptures and an extreme zeal for the English Bible. Upon receiving the Bible from Grafton, Cranmer said it was a “delightful surprise”, and supported the production of this English edition fully. On August 5th, 1537, Cranmer wrote a letter to Cromwell:

“You shall receive by the bringer thereof a bible in English, both of a new translation, and a new print, dedicated unto the king's majesty, as farther appeareth by a pistle unto his grace in the beginning of the book, which in mine opinion is very well done, and therefore I pray your lordship to read the same. And as for the translation, so far as I have read thereof, I like it better than any other translation heretofore made; yet not doubting but that there may and will be found some fault therein, as you know no man ever did or can do so well, but it may be from time to time amended. And forasmuch as the book is dedicated unto the king's grace and also great pains and labour taken in setting forth of the same ; I pray you my lord, that you will exhibit the book unto the king's highness, and to obtain of his grace, if you can, a license that the same may be sold and read of every person, without danger of any act, proclamation, or ordinance heretofore granted to the contrary, until such time as we the bishops shall set forth a better translation which I think will not be till a day after doomsday."

The Bible was graciously and quickly accepted by Cromwell, who also had a love for the Scriptures. Therefore, in thanks to this acceptance, Cranmer wrote Cromwell again only nine days after the original request.

“whereas I understand that your lordship, at my request, hath not only exhibited this bible which I sent unto you, to the king's majesty, but also hath obtained of his grace, that the same shall be allowed by his authority to be bought and read within this realm ; my lord for this your pain, taken in this behalf, I give unto you my most hearty thanks : assuring your lordship, for the contentation of my mind, you have shewed me more pleasure herein, than if you had given me a thousand pound ; and I doubt not but that hereby such fruit of good knowledge shall ensue, that it shall well appear hereafter, what high and acceptable service you have done unto God and the king."

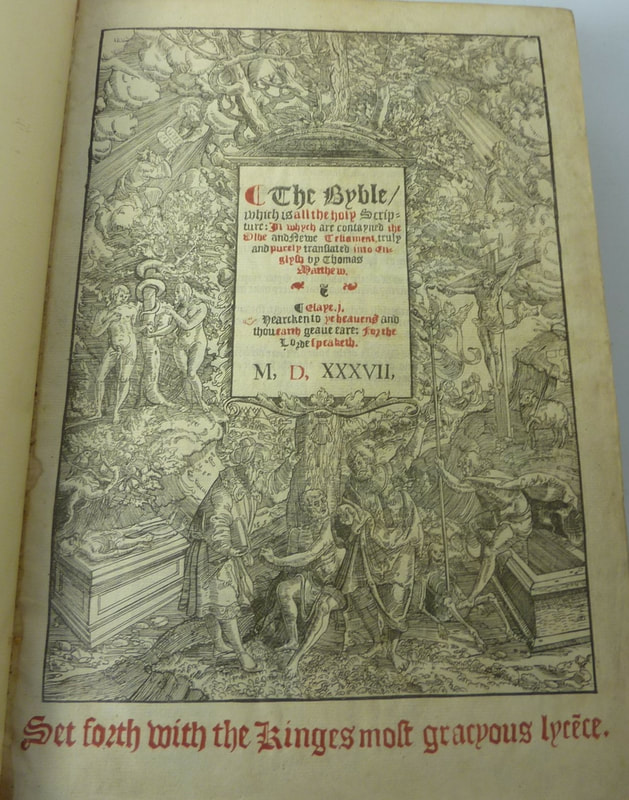

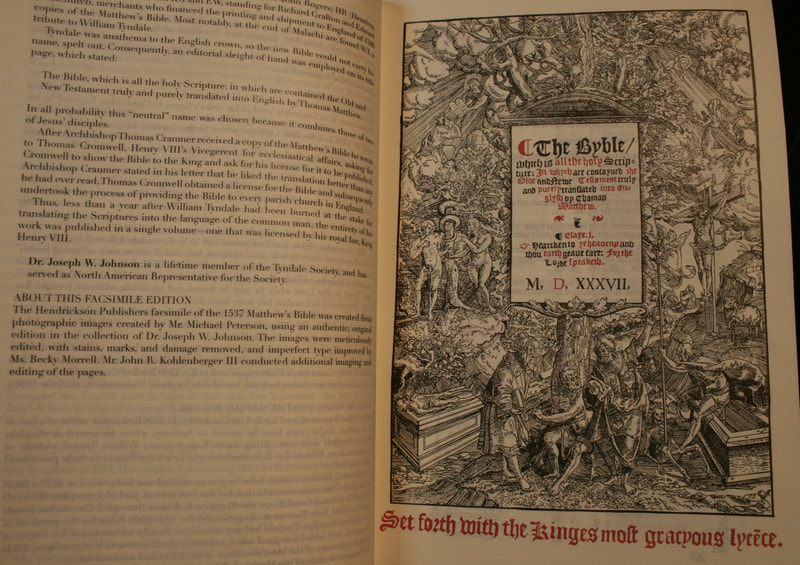

These extracts show how intensely Cranmer's mind was occupied in the setting forth of this edition of the Bible. It was therefore through the influence of Cranmer, the interposition of Cromwell, and the good will of Henry VIII, that the Bible of 1537 was the first to go forth with the royal privilege.

Upon receiving this acceptance and royal license of the king, Grafton added this authorization to his title page and completed the Bible. However, Grafton, having obtained this royal favor of the king, sought further to acquire the privy-seal, a copyright of this printing, so that he might have exclusive rights on account of the fact he had already invested over 500 pounds to produce 1,500 copies. Therefore, before Grafton released the Bibles for sale, he pursued further in a letter asking for these exclusive rights. Some people criticize Grafton for demanding these rights, saying he was only doing this for the money, but I disagree completely. Grafton had just started his press, and he wanted his first printing to be this English Bible. 500 pounds in those days is equivalent to over 420,000 dollars in our time. He had invested his life’s savings to compete this printing. Therefore, I do not think it selfish or greedy in any way for Grafton to request the privy-seal. In this letter, he writes to Cromwell pleading:

That the edition may go forth under the privy-seal, as a defense against pirated editions. He says he had already printed “fifteen hundred books complete," in large letter, and their sale was threatened by Dutch printers, who “will and doth go about the printing of the same work again in a lesser letter; to the intent that they may sell their little books better cheap than I can sell these great." Besides, he adds, that these printers would not only set forth a smaller volume, but one imperfect as to paper, ink, and correction. That the printing and correcting would be done by Dutch men, who could neither speak or write good English, and that they would not "bestow twenty or forty pounds to a Learned man to take pains in it, to have it well done."

On these grounds he seeks the authority of the privy-seal, with the exclusive right to print and sell these Bibles for the space of three years. Further, he requested that Cromwell would issue a royal injunction to the effect that every curate should be compelled to have one of these Bibles, and “that every Abby should have six to be laid in six several places;

“that not only the whole convent, but those who resorted thither, might have the opportunity of reading the same.”

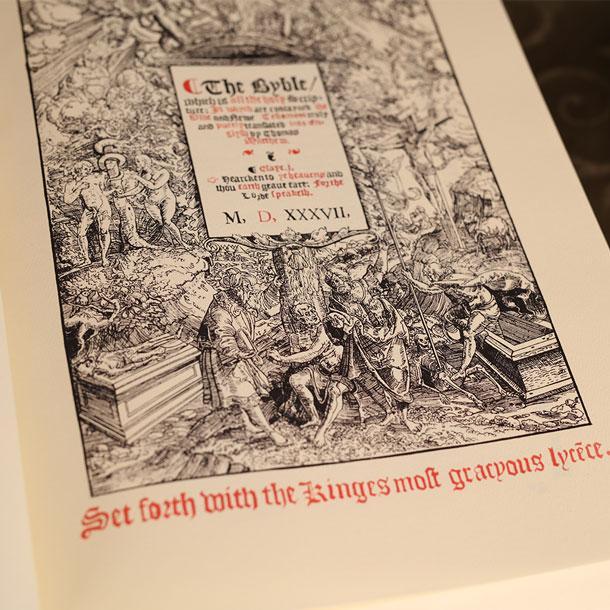

Grafton had great success, through the influence of Cromwell and the intervention of Cranmer, to obtain the king's license, which was inserted upon the title-page in red letters, thus: “Set forth by the Kings most gracious License." But as many refused to believe that the king had licensed it, he sought as above to have it go forth under the privy-seal. [1]

The request of Grafton was accepted, and he became the exclusive printer for the Matthew’s Bible, and later, because of the privy-seal, became the printer of the first authorized English Bible, known as The Great Bible of 1539.

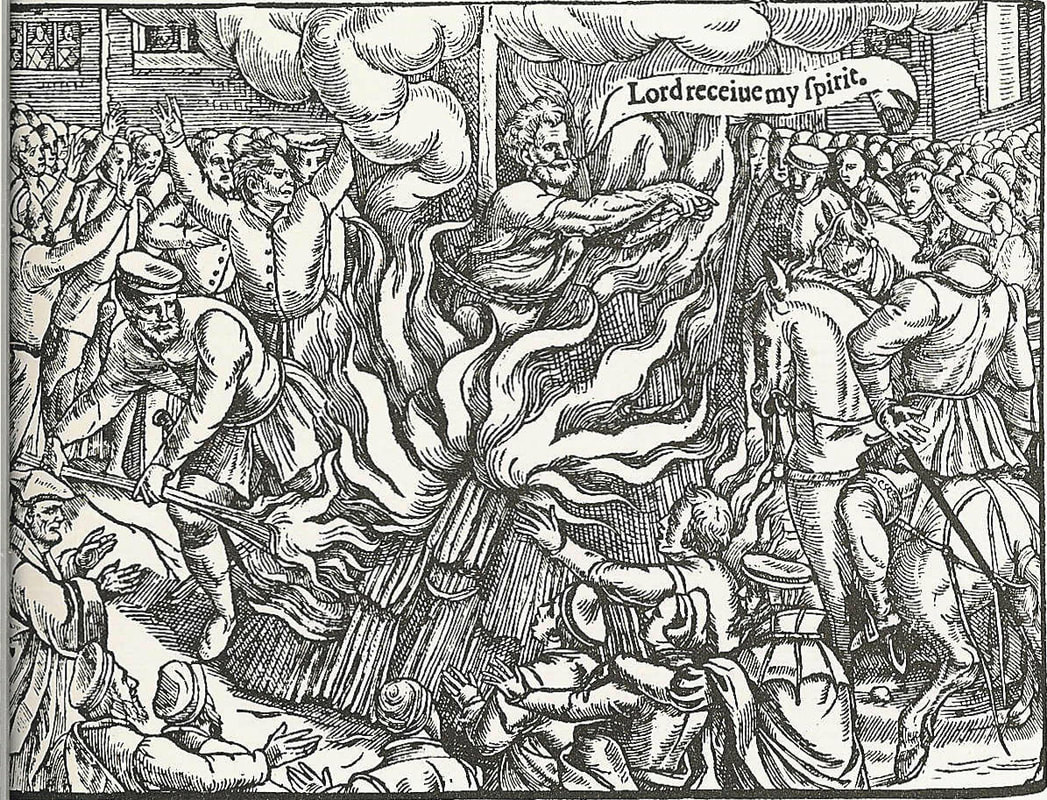

John Rogers would continue as a great man of the Reformation, finally giving his life to martyrdom, and committed to the flames in 1555 as the first Protestant martyr of Queen Mary, also known as “Bloody Mary”.

[1] The History of the English Bible by Blackford Condit 1896

The Bible was graciously and quickly accepted by Cromwell, who also had a love for the Scriptures. Therefore, in thanks to this acceptance, Cranmer wrote Cromwell again only nine days after the original request.

“whereas I understand that your lordship, at my request, hath not only exhibited this bible which I sent unto you, to the king's majesty, but also hath obtained of his grace, that the same shall be allowed by his authority to be bought and read within this realm ; my lord for this your pain, taken in this behalf, I give unto you my most hearty thanks : assuring your lordship, for the contentation of my mind, you have shewed me more pleasure herein, than if you had given me a thousand pound ; and I doubt not but that hereby such fruit of good knowledge shall ensue, that it shall well appear hereafter, what high and acceptable service you have done unto God and the king."

These extracts show how intensely Cranmer's mind was occupied in the setting forth of this edition of the Bible. It was therefore through the influence of Cranmer, the interposition of Cromwell, and the good will of Henry VIII, that the Bible of 1537 was the first to go forth with the royal privilege.

Upon receiving this acceptance and royal license of the king, Grafton added this authorization to his title page and completed the Bible. However, Grafton, having obtained this royal favor of the king, sought further to acquire the privy-seal, a copyright of this printing, so that he might have exclusive rights on account of the fact he had already invested over 500 pounds to produce 1,500 copies. Therefore, before Grafton released the Bibles for sale, he pursued further in a letter asking for these exclusive rights. Some people criticize Grafton for demanding these rights, saying he was only doing this for the money, but I disagree completely. Grafton had just started his press, and he wanted his first printing to be this English Bible. 500 pounds in those days is equivalent to over 420,000 dollars in our time. He had invested his life’s savings to compete this printing. Therefore, I do not think it selfish or greedy in any way for Grafton to request the privy-seal. In this letter, he writes to Cromwell pleading:

That the edition may go forth under the privy-seal, as a defense against pirated editions. He says he had already printed “fifteen hundred books complete," in large letter, and their sale was threatened by Dutch printers, who “will and doth go about the printing of the same work again in a lesser letter; to the intent that they may sell their little books better cheap than I can sell these great." Besides, he adds, that these printers would not only set forth a smaller volume, but one imperfect as to paper, ink, and correction. That the printing and correcting would be done by Dutch men, who could neither speak or write good English, and that they would not "bestow twenty or forty pounds to a Learned man to take pains in it, to have it well done."

On these grounds he seeks the authority of the privy-seal, with the exclusive right to print and sell these Bibles for the space of three years. Further, he requested that Cromwell would issue a royal injunction to the effect that every curate should be compelled to have one of these Bibles, and “that every Abby should have six to be laid in six several places;

“that not only the whole convent, but those who resorted thither, might have the opportunity of reading the same.”

Grafton had great success, through the influence of Cromwell and the intervention of Cranmer, to obtain the king's license, which was inserted upon the title-page in red letters, thus: “Set forth by the Kings most gracious License." But as many refused to believe that the king had licensed it, he sought as above to have it go forth under the privy-seal. [1]

The request of Grafton was accepted, and he became the exclusive printer for the Matthew’s Bible, and later, because of the privy-seal, became the printer of the first authorized English Bible, known as The Great Bible of 1539.

John Rogers would continue as a great man of the Reformation, finally giving his life to martyrdom, and committed to the flames in 1555 as the first Protestant martyr of Queen Mary, also known as “Bloody Mary”.

[1] The History of the English Bible by Blackford Condit 1896

1537 Matthew's Bible of John Rogers