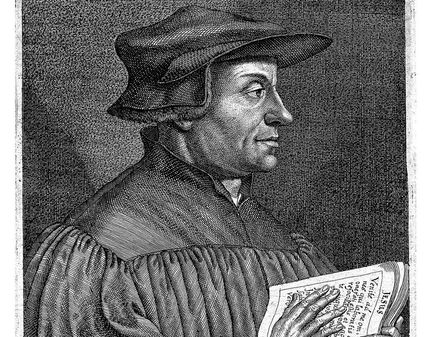

Ulrich Zwingli

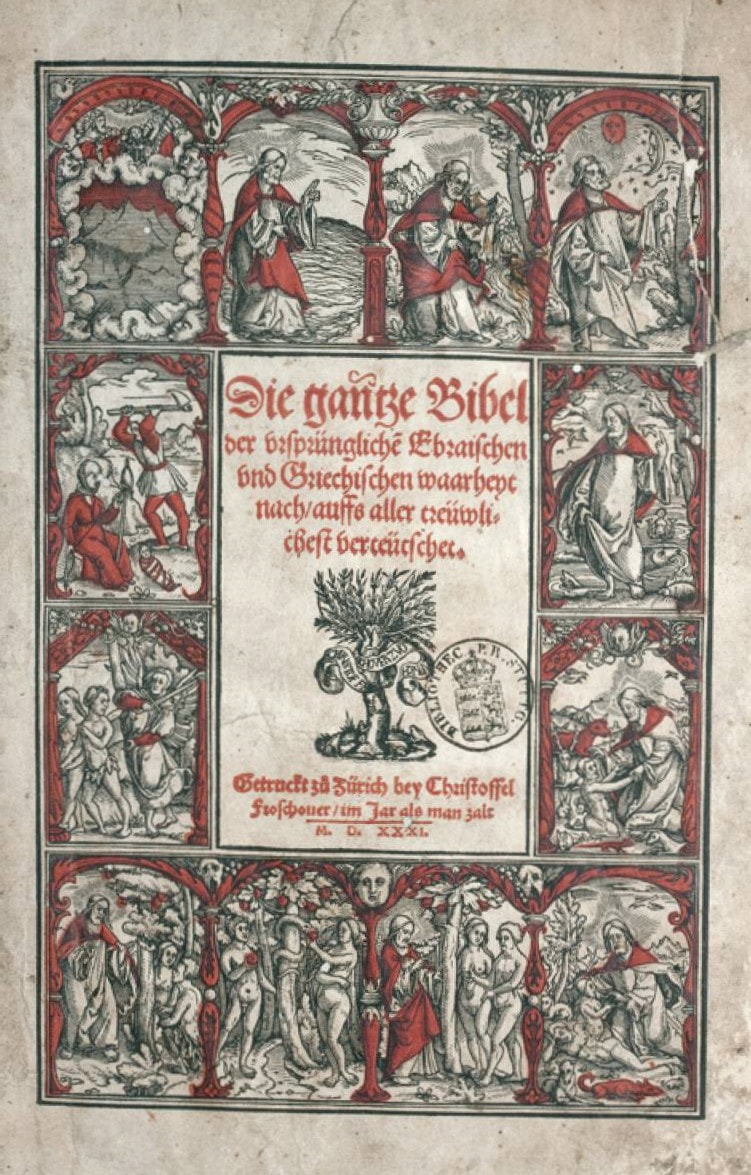

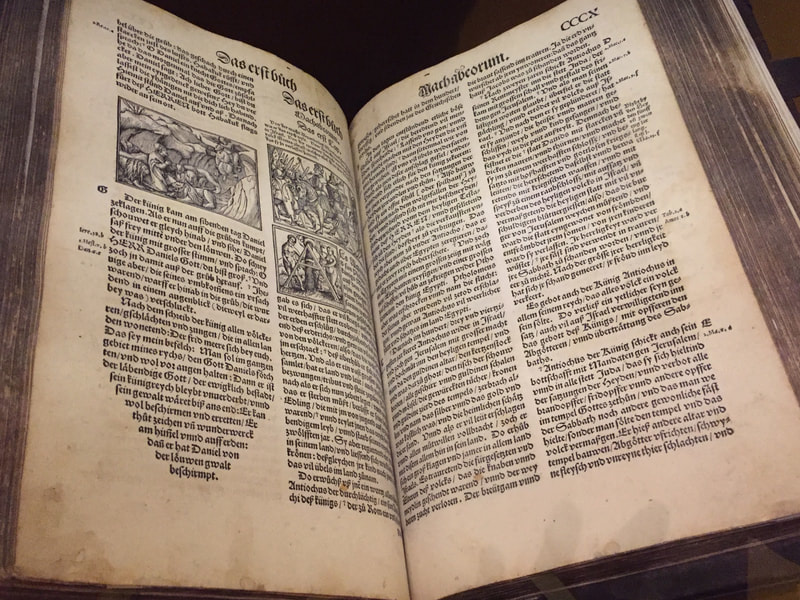

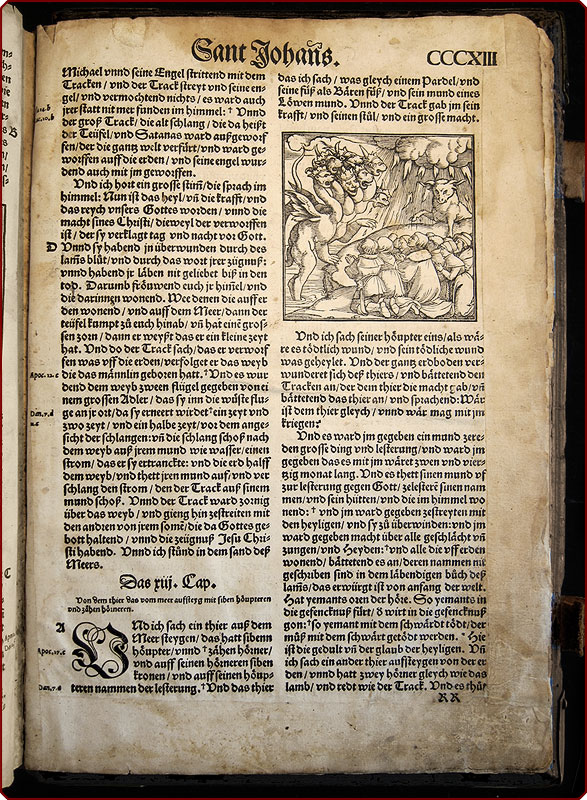

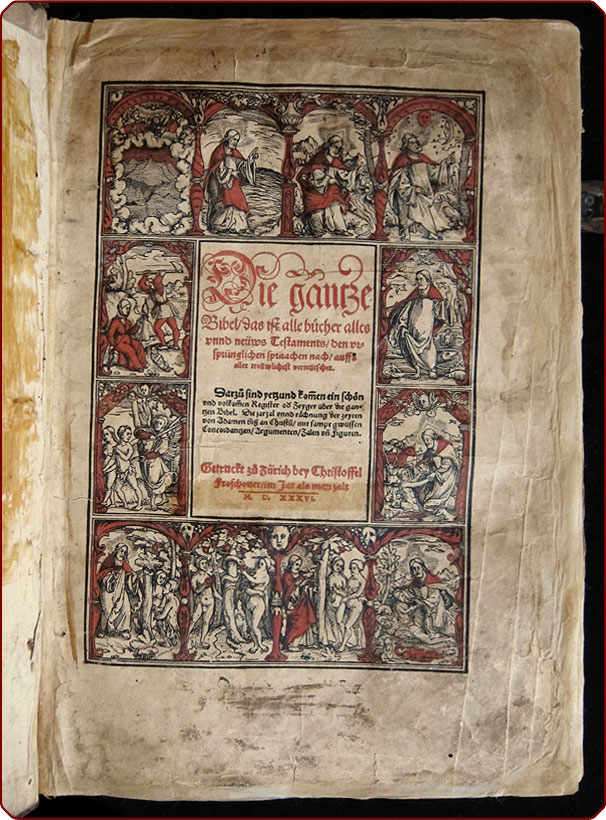

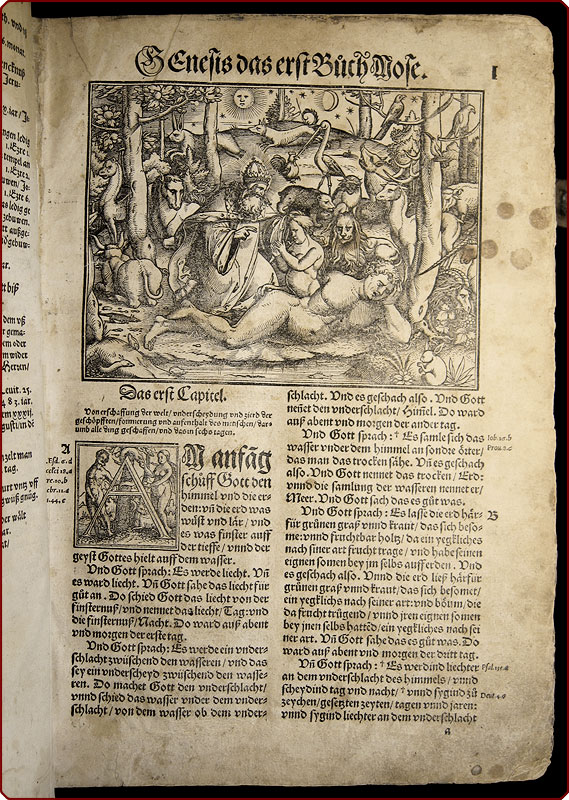

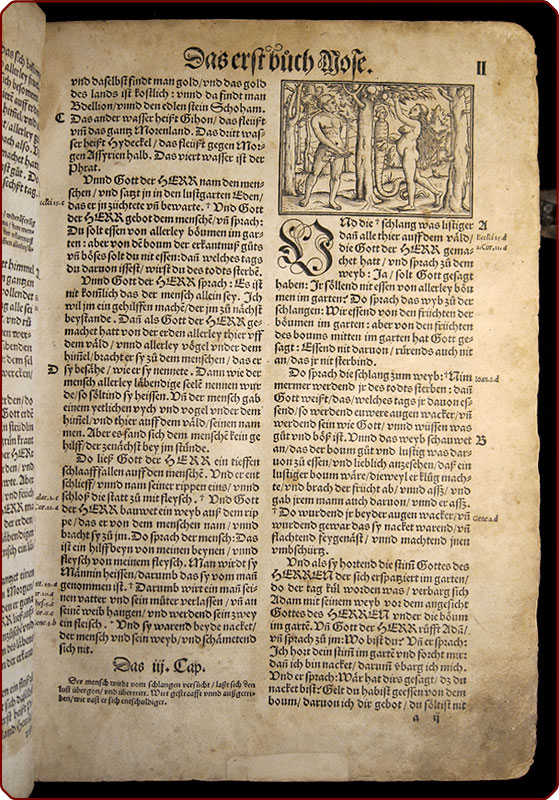

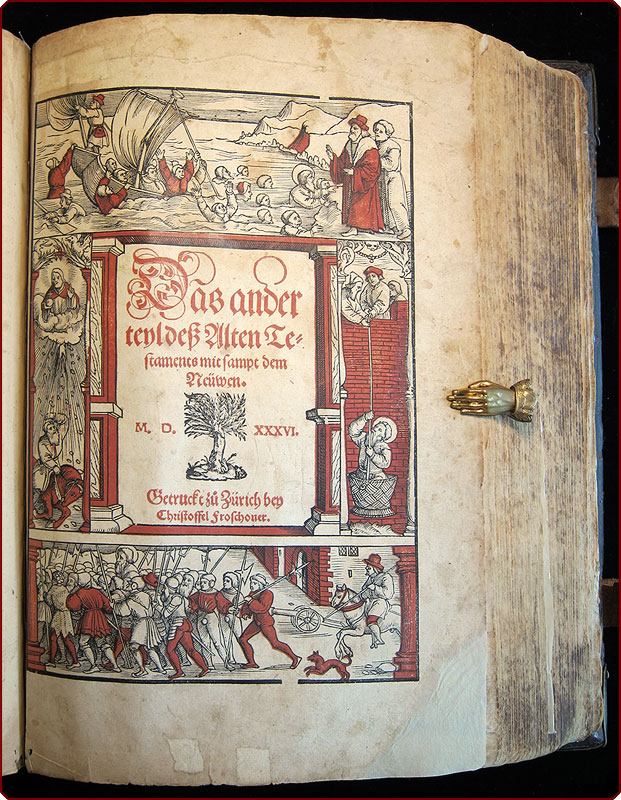

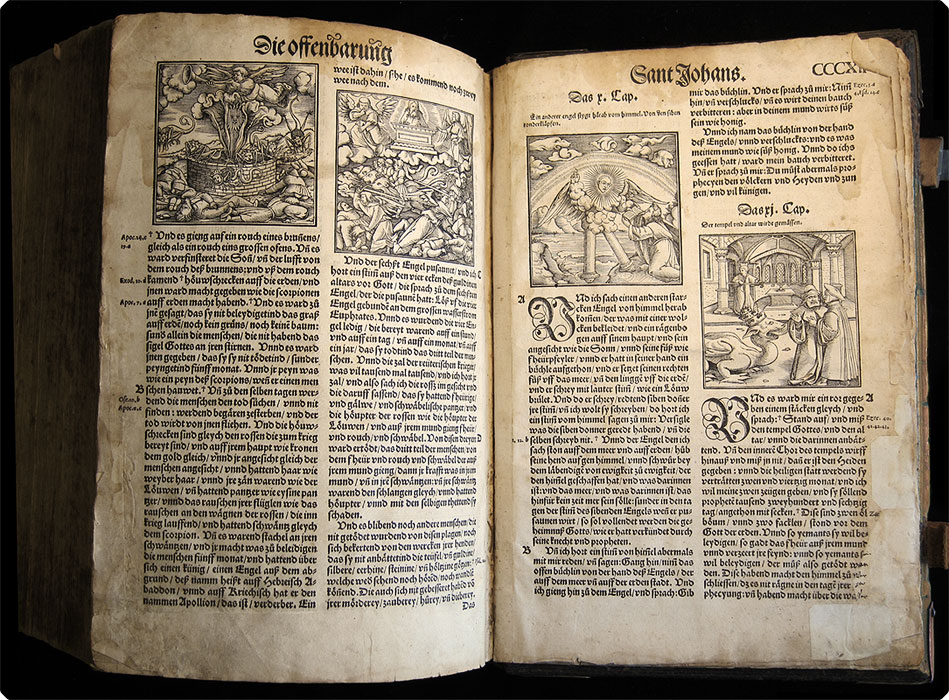

The 1531 Zurich Bible

lrich Zwingli, Father of the Swiss Reform-ation, born 1484 in Wildhaus, Switzerland, to a successful farmer in the Toggaburg Valley of the eastern lower Alps, and raised as a shepherd in the mountainous region of Switzerland.

His father and uncle, perceiving of young Ulrich’s intellect, sought to aid him with a tutor and as he became older, send him to the University of Basel. At Basel he became good friends with Reformer Capito. He also became acquainted with his life-long friend, Leo Juda. He graduated from the University of Basel in 1506. Word spread of this young master of arts from Basel. A town of Switzerland, not far from his native town of Wildhaus, asked him to be their priest. Zwingli accepted, he was ordained at Constance, and traveled to Glarus, and there took the responsibility of the priesthood. Zwingli felt he had an overwhelming obligation to his priestly duties, especially to his congregation. He was later quoted saying, “Though I was young, ecclesiastical duties inspired in me more fear than joy, because I knew, and remain convinced that I would give an account of the blood of the sheep which would perish as a consequence of my carelessness.”

His father and uncle, perceiving of young Ulrich’s intellect, sought to aid him with a tutor and as he became older, send him to the University of Basel. At Basel he became good friends with Reformer Capito. He also became acquainted with his life-long friend, Leo Juda. He graduated from the University of Basel in 1506. Word spread of this young master of arts from Basel. A town of Switzerland, not far from his native town of Wildhaus, asked him to be their priest. Zwingli accepted, he was ordained at Constance, and traveled to Glarus, and there took the responsibility of the priesthood. Zwingli felt he had an overwhelming obligation to his priestly duties, especially to his congregation. He was later quoted saying, “Though I was young, ecclesiastical duties inspired in me more fear than joy, because I knew, and remain convinced that I would give an account of the blood of the sheep which would perish as a consequence of my carelessness.”

Ulrich Zwingli 1484-1531

Ulrich Zwingli 1484-1531

Feeling this responsibility, Zwingli studied the Scriptures, determined to speak the Truth to his flock. This, in turn, inspired his interest in the Bible. In 1513, he began teaching himself Greek. He said, “I have resolved so to apply myself to the study of Greek, that none will be able to turn me from it but God. I do it not for fame, but from love to sacred literature. In order to be able to draw the doctrine of Jesus Christ from the very fountain of Truth.”[1]

In 1516, having a love for the writings of Erasmus, probably encouraged by his friend Capito, bought a copy of Erasmus's Greek New Testament. He copied Paul’s epistles by hand and memorized them in the original language, and then carried his little pocket edition of the Pauline epistles with him.[2] It was at this time, when Zwingli turned toward the Holy Scriptures, that Switzerland took its first step in the Reformation.

In this final year at Glarus, 1516, Zwingli came to an evangelical understanding of the Scriptures. He started preaching the Truth of the Gospel and when the question was asked if he was a follower of Luther, he responded by saying, “I had no knowledge of Luther’s ideas, I began to preach the same message Luther would soon proclaim. Before anyone in the area had ever heard of Luther, I began to preach the gospel of Christ in 1516… . I started preaching the gospel before I had even heard Luther’s name… . Luther, whose name I did not know for at least another two years, had definitely not instructed me. I followed holy Scripture alone.” Luther and Zwingli would eventually meet, but there were some differences between them that kept them from becoming close friends. Zwingli left Glarus and moved to Einsidlen. It was in the chapel of “our Lady of Einsidlen”, that he first proclaimed the Truth of Jesus Christ to this town. Some walked off in horror, while others sought the living Word of Truth. Word spread through the whole town of Einsidlen of this preacher and many people flocked to hear the message of the Gospel. After three years in Einsidlen, in the year 1518, the priestly seat of the church at Zurich had become vacant and Zwingli was the elected favorite to this vacancy. Overjoyed, but grieved to leave Einsidlen, on 27th of December 1518, Zwingli arrived at Zurich.

The people of Zurich were in need of the Truth, and for the first time, the Gospel was presented them as Zwingli expounded the Scriptures of the New Testament based on the original Greek. The Reformation message was rejected by many in the town of Zurich, but Zwingli stayed strong and immoveable, and slowly began to win the hearts of those in Zurich.

Zwingli grew in popularity with the people, and in 1529 he became involved in political leadership. Perhaps Zwingli’s downfall, and a major difference between his and Luther’s outlook, was his patriotic spirit toward his country. He was a devout pastor of his congregation, and had a heart for his people. In the same manner, he had a heart for his country. Zwingli desired a unity of faith and religious freedom in Switzerland. Thinking he could advance the Reformation through political affairs, Zwingli began participating in the occupation of the state, but this greatly distracted from his work as a preacher. It is true, God will use the political circumstances of the world to advance and protect His Word, but the political defense and spiritual development rarely comes from the same fountain. For example: Mordecai and Xerxes; Ezra, Nehemiah, and Artaxerxes; Wycliffe and the king of England, Edward III; Luther and the Elector Fredrick; to name a few, but seldom do we see the same leader, both of civil and spiritual matters, as was the case with Zwingli.

As the war commenced for the freedom of Switzerland, Zwingli would preach to the soldiers on the battlefield. He was fighting in the name of the Lord and the Glory of Christ. In his own words he said, “No doubt, it is not by human strength,” said he, “it is by the strength of God alone that the Word of the Lord should be upheld. But God often makes use of men as instruments to succor men. Let us therefore unite, and from the sources of the Rhino to Strasburg let us form but one people and one alliance.” I believe Zwingli, with all his heart, thought he was acting according to the will of God, and maybe he was, God is the only one who can judge this correctly.

However, “the weapons of our warfare are not carnal but mighty in God for pulling down strongholds,” (2 Corinthians 10:4). The early church did not oppose their persecutors with war, but through the Word of God and trust in Him. But Zwingli did not see victory in this way. The Emperor, Charles V, had made an alliance with the Pope, and Zwingli was convinced the only way to stop the advancement of the papacy was to defend the Word of God through war. It was from this time until his death, less than two years later, we see Zwingli transform from the Reformer of Switzerland to a general of his army. Zwingli, in a political point of view, is one of the greatest leaders of all time. Some even say this period of time was the highlight and pinnacle of his life.

Finally, war was decided, and the final battle commenced on the battlefield of Kappel, Switzerland. Zwingli, still leading his troops in the name of Jesus, fought for the liberty of the Swiss people. However, Zwingli was cut down by the sword and in October 1531, the great general died under a pear tree. Zurich retaliated with over 24,000 men, but the army of the papacy, authorized and empowered by the Emperor was too strong, and Switzerland fell into the hands of the Catholic Church. But the Truth would not be constrained. As D’ Aubigne says-

But the hopes of the Papists were vain: the cause of the Gospel, although humbled at this moment, was destined finally to gain a glorious victory. A cloud may hide the sun for a time; but the cloud passes and the sun reappears. Jesus Christ is always the same, and the gates of hell may triumph on the battle-field, but cannot prevail against his Church.[3]

Although Zwingli may have gone down in history as the great general and leader of the Swiss army, his greatest accomplishment was his contribution in translating the Swiss Bible. It is said that Zwingli translated the Bible with the help of Leo Jud, Zwingli’s life-long friend, but I believe it was the other way around. The Zurich Bible was published in 1531 by Christoph Froschauer, the same year as Zwingli’s death. We know the distractions Zwingli faced with war on the horizon, therefore, I would conjecture that Leo Jud was the driving force in the accomplishment of guiding the translated Bible into the Swiss language. However, it was their combined efforts, Zwingli and Jud, to bring the Swiss Bible into print. Zwingli, fluent in the original languages of Greek and Hebrew, and the determination of Leo Jud to embrace the task of the publication, resulted in the culmination of the what we know as the Zurich Bible.

[1] D’Aubigné, J. H. M. (1862). History of the Reformation in the Sixteenth Century. (H. Beveridge & H. White, Trans.) (Vol. 2, p. 220). Glasgow; London: William Collins; R. Groombridge & Sons.

[2] Payne, J. B. (1984). Zwingli and Luther—The Giant vs. Hercules. Christian History Magazine-Issue 4: Zwingli: Father of the Swiss Reformation.

[3] D’Aubigné, J. H. M. (1862). History of the Reformation in the Sixteenth Century. (Vol. 4, p. 392).

In 1516, having a love for the writings of Erasmus, probably encouraged by his friend Capito, bought a copy of Erasmus's Greek New Testament. He copied Paul’s epistles by hand and memorized them in the original language, and then carried his little pocket edition of the Pauline epistles with him.[2] It was at this time, when Zwingli turned toward the Holy Scriptures, that Switzerland took its first step in the Reformation.

In this final year at Glarus, 1516, Zwingli came to an evangelical understanding of the Scriptures. He started preaching the Truth of the Gospel and when the question was asked if he was a follower of Luther, he responded by saying, “I had no knowledge of Luther’s ideas, I began to preach the same message Luther would soon proclaim. Before anyone in the area had ever heard of Luther, I began to preach the gospel of Christ in 1516… . I started preaching the gospel before I had even heard Luther’s name… . Luther, whose name I did not know for at least another two years, had definitely not instructed me. I followed holy Scripture alone.” Luther and Zwingli would eventually meet, but there were some differences between them that kept them from becoming close friends. Zwingli left Glarus and moved to Einsidlen. It was in the chapel of “our Lady of Einsidlen”, that he first proclaimed the Truth of Jesus Christ to this town. Some walked off in horror, while others sought the living Word of Truth. Word spread through the whole town of Einsidlen of this preacher and many people flocked to hear the message of the Gospel. After three years in Einsidlen, in the year 1518, the priestly seat of the church at Zurich had become vacant and Zwingli was the elected favorite to this vacancy. Overjoyed, but grieved to leave Einsidlen, on 27th of December 1518, Zwingli arrived at Zurich.

The people of Zurich were in need of the Truth, and for the first time, the Gospel was presented them as Zwingli expounded the Scriptures of the New Testament based on the original Greek. The Reformation message was rejected by many in the town of Zurich, but Zwingli stayed strong and immoveable, and slowly began to win the hearts of those in Zurich.

Zwingli grew in popularity with the people, and in 1529 he became involved in political leadership. Perhaps Zwingli’s downfall, and a major difference between his and Luther’s outlook, was his patriotic spirit toward his country. He was a devout pastor of his congregation, and had a heart for his people. In the same manner, he had a heart for his country. Zwingli desired a unity of faith and religious freedom in Switzerland. Thinking he could advance the Reformation through political affairs, Zwingli began participating in the occupation of the state, but this greatly distracted from his work as a preacher. It is true, God will use the political circumstances of the world to advance and protect His Word, but the political defense and spiritual development rarely comes from the same fountain. For example: Mordecai and Xerxes; Ezra, Nehemiah, and Artaxerxes; Wycliffe and the king of England, Edward III; Luther and the Elector Fredrick; to name a few, but seldom do we see the same leader, both of civil and spiritual matters, as was the case with Zwingli.

As the war commenced for the freedom of Switzerland, Zwingli would preach to the soldiers on the battlefield. He was fighting in the name of the Lord and the Glory of Christ. In his own words he said, “No doubt, it is not by human strength,” said he, “it is by the strength of God alone that the Word of the Lord should be upheld. But God often makes use of men as instruments to succor men. Let us therefore unite, and from the sources of the Rhino to Strasburg let us form but one people and one alliance.” I believe Zwingli, with all his heart, thought he was acting according to the will of God, and maybe he was, God is the only one who can judge this correctly.

However, “the weapons of our warfare are not carnal but mighty in God for pulling down strongholds,” (2 Corinthians 10:4). The early church did not oppose their persecutors with war, but through the Word of God and trust in Him. But Zwingli did not see victory in this way. The Emperor, Charles V, had made an alliance with the Pope, and Zwingli was convinced the only way to stop the advancement of the papacy was to defend the Word of God through war. It was from this time until his death, less than two years later, we see Zwingli transform from the Reformer of Switzerland to a general of his army. Zwingli, in a political point of view, is one of the greatest leaders of all time. Some even say this period of time was the highlight and pinnacle of his life.

Finally, war was decided, and the final battle commenced on the battlefield of Kappel, Switzerland. Zwingli, still leading his troops in the name of Jesus, fought for the liberty of the Swiss people. However, Zwingli was cut down by the sword and in October 1531, the great general died under a pear tree. Zurich retaliated with over 24,000 men, but the army of the papacy, authorized and empowered by the Emperor was too strong, and Switzerland fell into the hands of the Catholic Church. But the Truth would not be constrained. As D’ Aubigne says-

But the hopes of the Papists were vain: the cause of the Gospel, although humbled at this moment, was destined finally to gain a glorious victory. A cloud may hide the sun for a time; but the cloud passes and the sun reappears. Jesus Christ is always the same, and the gates of hell may triumph on the battle-field, but cannot prevail against his Church.[3]

Although Zwingli may have gone down in history as the great general and leader of the Swiss army, his greatest accomplishment was his contribution in translating the Swiss Bible. It is said that Zwingli translated the Bible with the help of Leo Jud, Zwingli’s life-long friend, but I believe it was the other way around. The Zurich Bible was published in 1531 by Christoph Froschauer, the same year as Zwingli’s death. We know the distractions Zwingli faced with war on the horizon, therefore, I would conjecture that Leo Jud was the driving force in the accomplishment of guiding the translated Bible into the Swiss language. However, it was their combined efforts, Zwingli and Jud, to bring the Swiss Bible into print. Zwingli, fluent in the original languages of Greek and Hebrew, and the determination of Leo Jud to embrace the task of the publication, resulted in the culmination of the what we know as the Zurich Bible.

[1] D’Aubigné, J. H. M. (1862). History of the Reformation in the Sixteenth Century. (H. Beveridge & H. White, Trans.) (Vol. 2, p. 220). Glasgow; London: William Collins; R. Groombridge & Sons.

[2] Payne, J. B. (1984). Zwingli and Luther—The Giant vs. Hercules. Christian History Magazine-Issue 4: Zwingli: Father of the Swiss Reformation.

[3] D’Aubigné, J. H. M. (1862). History of the Reformation in the Sixteenth Century. (Vol. 4, p. 392).