1516

Erasmus Greek New Testament

ctober 31, 1517 is the popular commencement of the dawn of the Reformation; when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the Wittemburg door. But the reform, in which Martin Luther was about to advance, rested on the foundation that was laid just one year previous; the printed Greek New Testament produced by Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1469-1536.

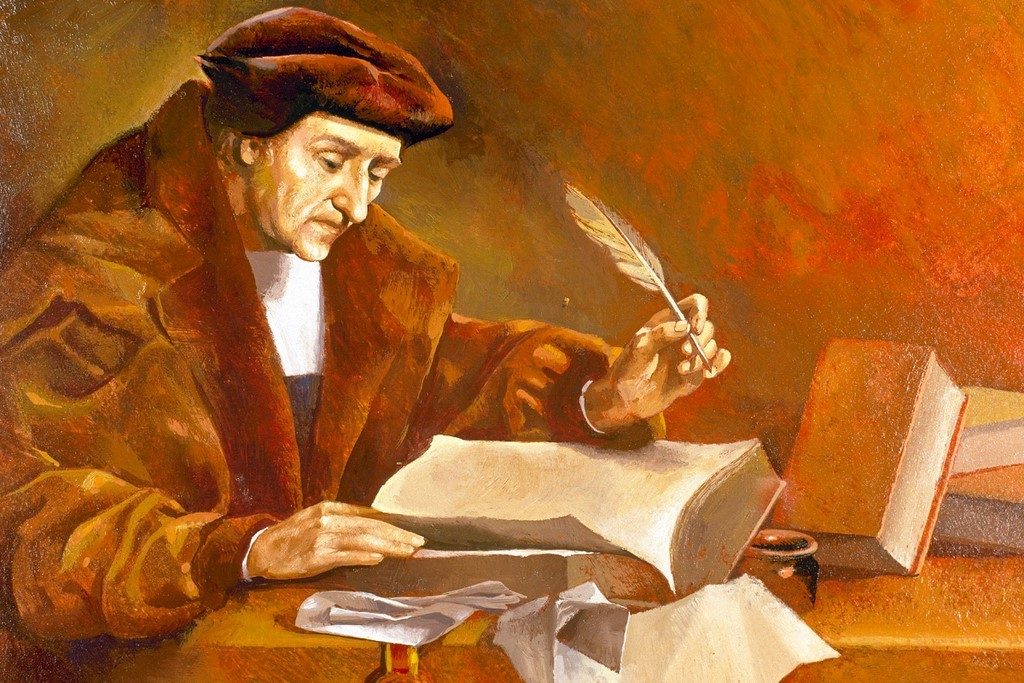

Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1469-1536

Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1469-1536

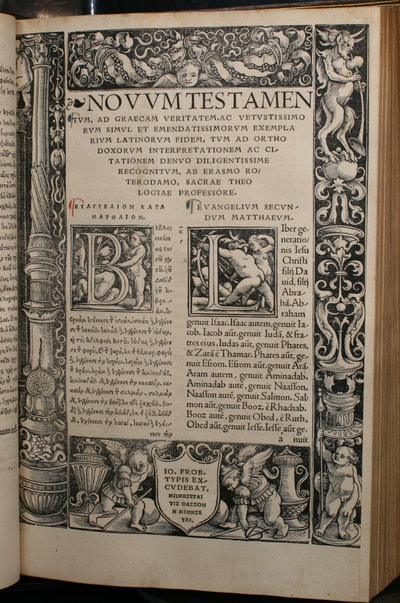

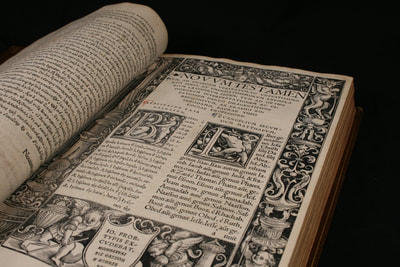

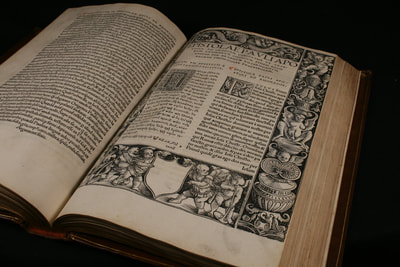

The New Testament, brought to light in the original Greek tongue, was now compiled and made available for mankind to study and learn. The learned scholar, although working under and deeply associated with the Roman Catholic Church, declared his disagreement with those who wanted to keep the Scriptures from the common people. He said, “If only the farmer would sing something from them at his plow, the weaver move his shuttle to their tune, the traveler lighten the boredom of his journey with Scriptural stories!” Little did he know, the work he was about to produce would change the world forever. This Greek New Testament, in printed form, would become the standard of the New Testament, launching the translations of Martin Luther and William Tyndale into the world. Thus, fulfilling his dream, that all men would read the Bible for themselves in their common language. His new “study Bible” had two main parts, the Greek text and a revised Latin edition, more elegant and accurate than the traditional translation of Jerome’s Latin Vulgate. Erasmus prefaced this monumental work of scholarship with an exhortation to Bible study. The New Testament, he proclaimed, contains the “philosophy of Christ,” a simple and accessible teaching with the power to transform lives.

Born in Rotterdam, Erasmus spent his life traveling throughout Europe. From 1499-1505, Erasmus traveled to France and Germany studying the New Testament in the original Greek, along with the writings of Origen. In 1506 Erasmus traveled to Bologna, Italy. It was here he met Aldus Manutius, an Italian printer, who enriched this scholar with Byzantine manuscripts of the Greek New Testament and other ancient writings. In 1509, Erasmus was invited to England where he met his life-long friend, Thomas More, humanist and scholar John Colet, and the young, soon to be king Henry VIII. It was here in England where he spent about five years, 1509-1514, in Cambridge, doing much of the work on his New Testament. After losing favor in England, the scholar of Rotterdam journeyed to Basle, Switzerland to meet printer, Johann Froben. It was here the Greek New Testament was brought to light and transferred onto printed pages.

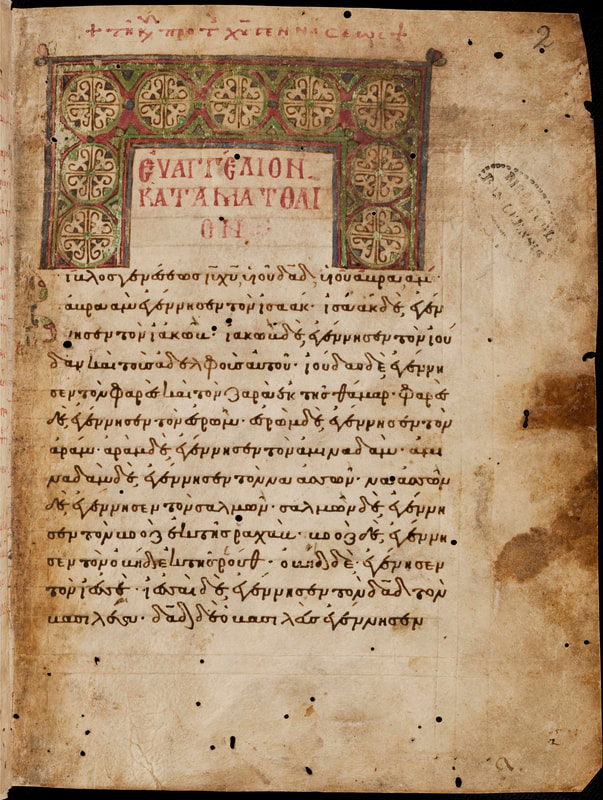

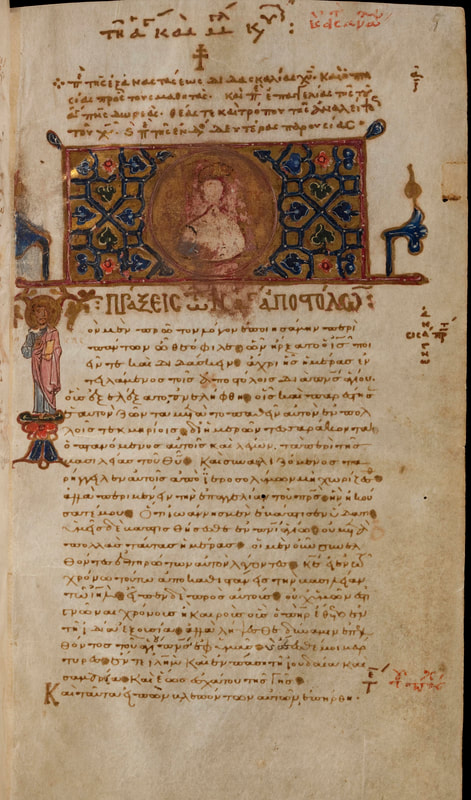

Erasmus chose seven Byzantine Greek manuscripts to transcribe and produce his Greek New Testament. The Codex Vatincanus was available at this time, being discovered in the 15th century, but I find it most interesting and significant that Erasmus specifically chose the Byzantine texts rather than anything from Alexandria. I believe Erasmus knew of the falsities of these texts and chose to avoid them. In Basel, there was another text available, the Codex Basilensis, but Erasmus chose not to use this either. My conjecture is the text is of the uncial type, all capital letters, instead of the minuscule, a smaller cursive text. All the texts Erasmus used was of the minuscule type.

It is significant to mention, that although the Byzantine Empire had its faults, they were the one chosen by God to preserve the Greek text of the New Testament. Despite the fact of the separation and excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church, known as the Great Schism of 1054, considered in Christian History as an abominable event, I conjecture this was the hand of God at work to preserve His Word. The excommunication and separation from the Catholic Church was a necessary event in the preservation of the Word of God, not an abomination to Christian history. The secular world views the Roman Catholic Church as the pinnacle of Christian history. For instance, if one were to search “Christian History”, on the internet, the history of the Roman Catholic Church is among the top results. However, what the world does not realize is, not all, but most leaders of the Catholic Church during the Dark Ages, specifically from 1,000 – 1,600, were not even Christian. They used the power and wealth of the Catholic see to promote and exalt themselves. The true roots to Christianity lie in the preservation and proclamation of the Word of God, such as those we have already mentioned, namely those in the North, not allowing them to be succumbed to the traditions of the Church, those in the East preserving the sacred Greek text of the New Testament, and the Masoretes in Jerusalem preserving the Masoretic text of the Old Testament. All working together by the hand of God to usher His Word back to light.

Erasmus’ first edition of the Greek New Testament went to the press in October 1515, and was completed in March of 1516. In 1519 a second edition was produced which corrected many typographical errors that had occurred during the printing process. Then, in 1522, having five additional Greek manuscript available to him, including the Codex Montfortianus, or as Erasmus names it, Codex Britannicus, a 13th century minuscule, Erasmus published his third edition of the Greek New Testament. In this third edition, Erasmus changed the Greek font slightly, and added capital letters at the beginning of sentences, but textually it was the same as the 1519 edition with the exception of one significant addition known as the “Johannine Comma”, namely 1John 5:7-8, in which we will dedicate some time later to discuss this illusive statement.

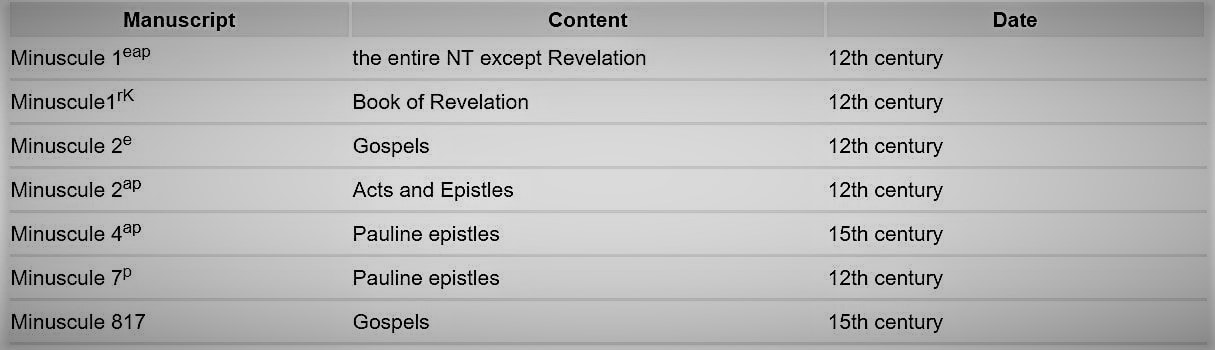

Below is a list of the seven Byzantine manuscripts used of Erasmus in his 1516 edition

Born in Rotterdam, Erasmus spent his life traveling throughout Europe. From 1499-1505, Erasmus traveled to France and Germany studying the New Testament in the original Greek, along with the writings of Origen. In 1506 Erasmus traveled to Bologna, Italy. It was here he met Aldus Manutius, an Italian printer, who enriched this scholar with Byzantine manuscripts of the Greek New Testament and other ancient writings. In 1509, Erasmus was invited to England where he met his life-long friend, Thomas More, humanist and scholar John Colet, and the young, soon to be king Henry VIII. It was here in England where he spent about five years, 1509-1514, in Cambridge, doing much of the work on his New Testament. After losing favor in England, the scholar of Rotterdam journeyed to Basle, Switzerland to meet printer, Johann Froben. It was here the Greek New Testament was brought to light and transferred onto printed pages.

Erasmus chose seven Byzantine Greek manuscripts to transcribe and produce his Greek New Testament. The Codex Vatincanus was available at this time, being discovered in the 15th century, but I find it most interesting and significant that Erasmus specifically chose the Byzantine texts rather than anything from Alexandria. I believe Erasmus knew of the falsities of these texts and chose to avoid them. In Basel, there was another text available, the Codex Basilensis, but Erasmus chose not to use this either. My conjecture is the text is of the uncial type, all capital letters, instead of the minuscule, a smaller cursive text. All the texts Erasmus used was of the minuscule type.

It is significant to mention, that although the Byzantine Empire had its faults, they were the one chosen by God to preserve the Greek text of the New Testament. Despite the fact of the separation and excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church, known as the Great Schism of 1054, considered in Christian History as an abominable event, I conjecture this was the hand of God at work to preserve His Word. The excommunication and separation from the Catholic Church was a necessary event in the preservation of the Word of God, not an abomination to Christian history. The secular world views the Roman Catholic Church as the pinnacle of Christian history. For instance, if one were to search “Christian History”, on the internet, the history of the Roman Catholic Church is among the top results. However, what the world does not realize is, not all, but most leaders of the Catholic Church during the Dark Ages, specifically from 1,000 – 1,600, were not even Christian. They used the power and wealth of the Catholic see to promote and exalt themselves. The true roots to Christianity lie in the preservation and proclamation of the Word of God, such as those we have already mentioned, namely those in the North, not allowing them to be succumbed to the traditions of the Church, those in the East preserving the sacred Greek text of the New Testament, and the Masoretes in Jerusalem preserving the Masoretic text of the Old Testament. All working together by the hand of God to usher His Word back to light.

Erasmus’ first edition of the Greek New Testament went to the press in October 1515, and was completed in March of 1516. In 1519 a second edition was produced which corrected many typographical errors that had occurred during the printing process. Then, in 1522, having five additional Greek manuscript available to him, including the Codex Montfortianus, or as Erasmus names it, Codex Britannicus, a 13th century minuscule, Erasmus published his third edition of the Greek New Testament. In this third edition, Erasmus changed the Greek font slightly, and added capital letters at the beginning of sentences, but textually it was the same as the 1519 edition with the exception of one significant addition known as the “Johannine Comma”, namely 1John 5:7-8, in which we will dedicate some time later to discuss this illusive statement.

Below is a list of the seven Byzantine manuscripts used of Erasmus in his 1516 edition

The following is a text from, in my opinion, the best book concerning the Reformation, written by Jean-Henri Merle D’Aubigné, 1862, The History of the Reformation in the Sixteenth Century., This information is vital to understanding the history of the Bible, and it is impossible for me to improve upon his text:

When Erasmus published this work, at the dawn, so to say, of modern times, he did not see all its scope. Had he foreseen it, he would perhaps have recoiled in alarm. He saw indeed that there was a great work to be done, but he believed that all good men would unite to do it with common accord. “A spiritual temple must be raised in desolated Christendom,” said he. “The mighty of this world will contribute towards it their marble, their ivory, and their gold; I who am poor and humble offer the foundation stone,” and he laid down before the world his edition of the Greek Testament. Then glancing disdainfully at the traditions of men, he said: “It is not from human reservoirs, fetid with stagnant waters, that we should draw the doctrine of salvation; but from the pure and abundant streams that flow from the heart of God.” And when some of his suspicious friends spoke to him of the difficulties of the times, he replied: “If the ship of the church is to be saved from being swallowed up by the tempest, there is only one anchor that can save it: it is the heavenly word, which, issuing from the bosom of the Father, lives, speaks, and works still in the Gospel.” These noble sentiments served as an introduction to those blessed pages which were to reform the world.

The New Testament in Greek and Latin had hardly appeared when it was received by all men of upright mind with unprecedented enthusiasm. Never had any book produced such a sensation. It was in every hand: men struggled to procure it, read it eagerly, and would even kiss it. The words it contained enlightened every heart. But a reaction soon took place. Traditional Catholicism uttered a cry from the depths of its noisome pools, (to use Erasmus’s figure). Franciscans and Dominicans, priests and bishops, not daring to attack the educated and well-born, went among the ignorant populace, and endeavoured by their tales and clamours to stir up susceptible women and credulous men. “Here are horrible heresies,” they exclaimed, “here are frightful antichrists! If this book be tolerated it will be the death of the papacy!”—“We must drive this man from the university,” said one. “We must turn him out of the church,” added another. “The public places re-echoed with their howlings,” said Erasmus. The firebrands tossed by their furious hands were raising fires in every quarter; and the flames kindled in a few obscure convents threatened to spread over the whole country.

This irritation was not without a cause. The book, indeed, contained nothing but Latin and Greek; but this first step seemed to augur another—the translation of the Bible into the vulgar tongue. Erasmus loudly called for it. “Perhaps it may be necessary to conceal the secrets of kings,” he remarked, “but we must publish the mysteries of Christ. The Holy Scriptures, translated into all languages, should be read not only by the Scotch and Irish, but even by Turks and Saracens. The husbandman should sing them as he holds the handle of his plough, the weaver repeat them as he plies his shuttle, and the wearied traveler, halting on his journey, refresh him under some shady tree by these Godly narratives.” These words prefigured a golden age after the iron age of popery. A number of Christian families in Britain and on the continent, were soon to realize these evangelical forebodings, and England after three centuries was to endeavor to carry them out for the benefit of all the nations on the face of the earth.

The priests saw the danger, and by a skillful maneuver, instead of finding fault with the Greek Testament, attacked the translation and the translator. “He has corrected the Vulgate,” they said, “and puts himself in the place of Saint Jerome. He sets aside a work authorized by the consent of ages and inspired by the Holy Ghost. What audacity!” And then, turning over the pages, they pointed out the most odious passages: “Look here! this book calls upon men to repent, instead of requiring them, as the Vulgate does, to do penance!” (Matt. 4:17.) The priests thundered against him from their pulpits: “This man has committed the unpardonable sin,” they asserted; “for he maintains that there is nothing in common between the Holy Ghost and the monks—that they are logs rather than men!” These simple remarks were received with a general laugh; but the priests, in no wise disconcerted, cried out all the louder: “He’s a heretic, an heresiarch, a forger! he’s a goose … what do I say? he’s a very antichrist!”

It was not sufficient for the papal janissaries to make war in the plain, they must carry it to the higher ground. Was not the king a friend of Erasmus? If he should declare himself a patron of the Greek and Latin Testament, what an awful calamity!… After having agitated the cloisters, towns, and universities, they resolved to protest against it boldly, even in Henry VIII’s presence. They thought: “If he is won, all is won.”

Erasmus was astonished at these discussions. He had imagined the season to be most favorable. “Everything looks peaceful,” he had said to himself; “now is the time to launch my Greek Testament into the learned world.” As well might the sun rise upon the earth, and no one see it! At that very hour God was raising up a monk at Wittemberg who would lift the trumpet to his lips, and proclaim the new day.

Nothing was more important at the dawn of the Reformation than the publication of the Testament of Jesus Christ in the original language. Never had Erasmus worked so carefully. “If I told what sweat it cost me, no one would believe me.” He had collated many Greek MSS. of the New Testament, and was surrounded by all the commentaries and translations, by the writings of Origen, Cyprian, Ambrose, Basil, Chrysostom, Cyril, Jerome, and Augustine. Hic sum in campo meo! he exclaimed as he sat in the midst of his books. He had investigated the texts according to the principles of sacred criticism. When a knowledge of Hebrew was necessary, he had consulted Capito and more particularly Oecolampadius. He had corrected the amphibologies, obscurities, hebraisms, and barbarisms of the Vulgate; and had caused a list to be printed of the errors in that version.

“We must restore the pure text of the word of God,” he had said; and when he heard the maledictions of the priests, he had exclaimed: “I call God to witness, I thought I was doing a work acceptable to the Lord and necessary to the cause of Christ.” Nor in this was he deceived.

When Erasmus published this work, at the dawn, so to say, of modern times, he did not see all its scope. Had he foreseen it, he would perhaps have recoiled in alarm. He saw indeed that there was a great work to be done, but he believed that all good men would unite to do it with common accord. “A spiritual temple must be raised in desolated Christendom,” said he. “The mighty of this world will contribute towards it their marble, their ivory, and their gold; I who am poor and humble offer the foundation stone,” and he laid down before the world his edition of the Greek Testament. Then glancing disdainfully at the traditions of men, he said: “It is not from human reservoirs, fetid with stagnant waters, that we should draw the doctrine of salvation; but from the pure and abundant streams that flow from the heart of God.” And when some of his suspicious friends spoke to him of the difficulties of the times, he replied: “If the ship of the church is to be saved from being swallowed up by the tempest, there is only one anchor that can save it: it is the heavenly word, which, issuing from the bosom of the Father, lives, speaks, and works still in the Gospel.” These noble sentiments served as an introduction to those blessed pages which were to reform the world.

The New Testament in Greek and Latin had hardly appeared when it was received by all men of upright mind with unprecedented enthusiasm. Never had any book produced such a sensation. It was in every hand: men struggled to procure it, read it eagerly, and would even kiss it. The words it contained enlightened every heart. But a reaction soon took place. Traditional Catholicism uttered a cry from the depths of its noisome pools, (to use Erasmus’s figure). Franciscans and Dominicans, priests and bishops, not daring to attack the educated and well-born, went among the ignorant populace, and endeavoured by their tales and clamours to stir up susceptible women and credulous men. “Here are horrible heresies,” they exclaimed, “here are frightful antichrists! If this book be tolerated it will be the death of the papacy!”—“We must drive this man from the university,” said one. “We must turn him out of the church,” added another. “The public places re-echoed with their howlings,” said Erasmus. The firebrands tossed by their furious hands were raising fires in every quarter; and the flames kindled in a few obscure convents threatened to spread over the whole country.

This irritation was not without a cause. The book, indeed, contained nothing but Latin and Greek; but this first step seemed to augur another—the translation of the Bible into the vulgar tongue. Erasmus loudly called for it. “Perhaps it may be necessary to conceal the secrets of kings,” he remarked, “but we must publish the mysteries of Christ. The Holy Scriptures, translated into all languages, should be read not only by the Scotch and Irish, but even by Turks and Saracens. The husbandman should sing them as he holds the handle of his plough, the weaver repeat them as he plies his shuttle, and the wearied traveler, halting on his journey, refresh him under some shady tree by these Godly narratives.” These words prefigured a golden age after the iron age of popery. A number of Christian families in Britain and on the continent, were soon to realize these evangelical forebodings, and England after three centuries was to endeavor to carry them out for the benefit of all the nations on the face of the earth.

The priests saw the danger, and by a skillful maneuver, instead of finding fault with the Greek Testament, attacked the translation and the translator. “He has corrected the Vulgate,” they said, “and puts himself in the place of Saint Jerome. He sets aside a work authorized by the consent of ages and inspired by the Holy Ghost. What audacity!” And then, turning over the pages, they pointed out the most odious passages: “Look here! this book calls upon men to repent, instead of requiring them, as the Vulgate does, to do penance!” (Matt. 4:17.) The priests thundered against him from their pulpits: “This man has committed the unpardonable sin,” they asserted; “for he maintains that there is nothing in common between the Holy Ghost and the monks—that they are logs rather than men!” These simple remarks were received with a general laugh; but the priests, in no wise disconcerted, cried out all the louder: “He’s a heretic, an heresiarch, a forger! he’s a goose … what do I say? he’s a very antichrist!”

It was not sufficient for the papal janissaries to make war in the plain, they must carry it to the higher ground. Was not the king a friend of Erasmus? If he should declare himself a patron of the Greek and Latin Testament, what an awful calamity!… After having agitated the cloisters, towns, and universities, they resolved to protest against it boldly, even in Henry VIII’s presence. They thought: “If he is won, all is won.”

Erasmus was astonished at these discussions. He had imagined the season to be most favorable. “Everything looks peaceful,” he had said to himself; “now is the time to launch my Greek Testament into the learned world.” As well might the sun rise upon the earth, and no one see it! At that very hour God was raising up a monk at Wittemberg who would lift the trumpet to his lips, and proclaim the new day.

Nothing was more important at the dawn of the Reformation than the publication of the Testament of Jesus Christ in the original language. Never had Erasmus worked so carefully. “If I told what sweat it cost me, no one would believe me.” He had collated many Greek MSS. of the New Testament, and was surrounded by all the commentaries and translations, by the writings of Origen, Cyprian, Ambrose, Basil, Chrysostom, Cyril, Jerome, and Augustine. Hic sum in campo meo! he exclaimed as he sat in the midst of his books. He had investigated the texts according to the principles of sacred criticism. When a knowledge of Hebrew was necessary, he had consulted Capito and more particularly Oecolampadius. He had corrected the amphibologies, obscurities, hebraisms, and barbarisms of the Vulgate; and had caused a list to be printed of the errors in that version.

“We must restore the pure text of the word of God,” he had said; and when he heard the maledictions of the priests, he had exclaimed: “I call God to witness, I thought I was doing a work acceptable to the Lord and necessary to the cause of Christ.” Nor in this was he deceived.

Thus, the foundation of the Reformation was built. Though still in a language of scholars, this unified the New Testament, making it a vital stepping stone to the publications of the Word of God in the common tongue. Erasmus named his work, Novum Instrumentum, Latin for “a new tool”. He would go on to publish four more editions of his Greek New Testament, totaling five editions in all, of which, the second in 1519 and the third in 1522 would be used by Martin Luther and William Tyndale respectively, to translate their Bibles into the common tongue, the German of Luther and the English of Tyndale.

There are many people today who speak ill of Erasmus, saying he did not have the determination, or the heroic tendencies of a Reformer. But God used this man to shape the foundation of the reformation soon to come. Though this scholar did not have the courage of Luther, he didn’t need to. God had Martin Luther for this task. The reformation was too big for just one man to take on. The success of the reformation had mainly to do with the diversity of men throughout the whole of Europe, men led of the Holy Spirit, working together in a common goal, to bring the Word of God to light. God chose Erasmus to be that man who would secure the foundation of the Word of God, the Bible in the original tongue.

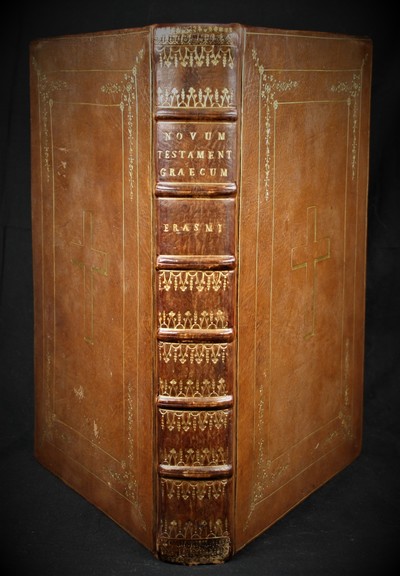

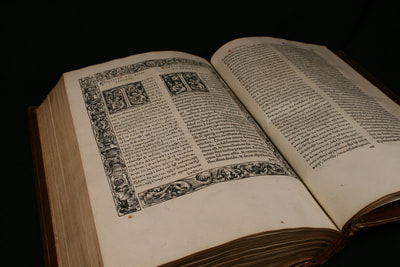

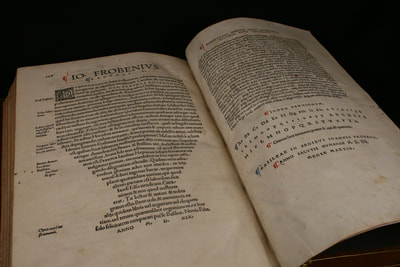

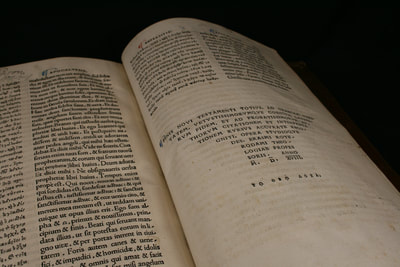

Below is an example of the 1519 Erasmus Greek New Testament for sale by Books of Truth

There are many people today who speak ill of Erasmus, saying he did not have the determination, or the heroic tendencies of a Reformer. But God used this man to shape the foundation of the reformation soon to come. Though this scholar did not have the courage of Luther, he didn’t need to. God had Martin Luther for this task. The reformation was too big for just one man to take on. The success of the reformation had mainly to do with the diversity of men throughout the whole of Europe, men led of the Holy Spirit, working together in a common goal, to bring the Word of God to light. God chose Erasmus to be that man who would secure the foundation of the Word of God, the Bible in the original tongue.

Below is an example of the 1519 Erasmus Greek New Testament for sale by Books of Truth

1519 Erasmus Digital Ebook Preview

to purchase the complete Bible in Digital Ebook with High Res PDF downloads click here

to purchase the complete Bible in Digital Ebook with High Res PDF downloads click here