French Translations

s the hand of God was working through Martin Luther in Germany, the Holy Spirt was also moving on those in France. One absolutely astounding fact to understand in the Reformation of the Sixteenth Century is the uniform work of the Holy Spirit effectively engaged in the whole of Europe, namely Germany, Switzerland, England, and France. The Reformation was not accomplished my merely one man, but One Holy Spirit, working through many people and many countries to unite His Word and bring the Light to the World.

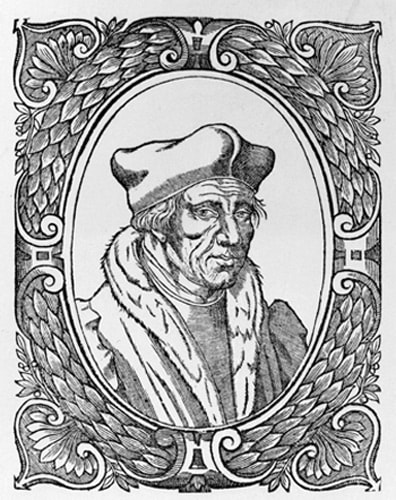

LeFevre d’Etaples

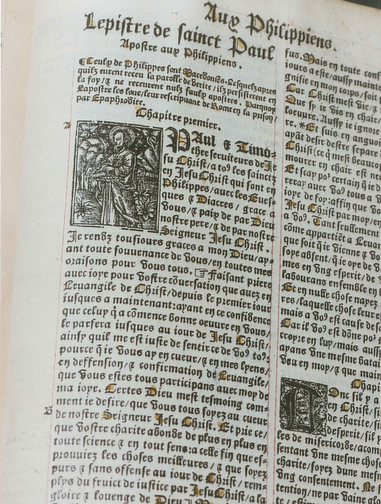

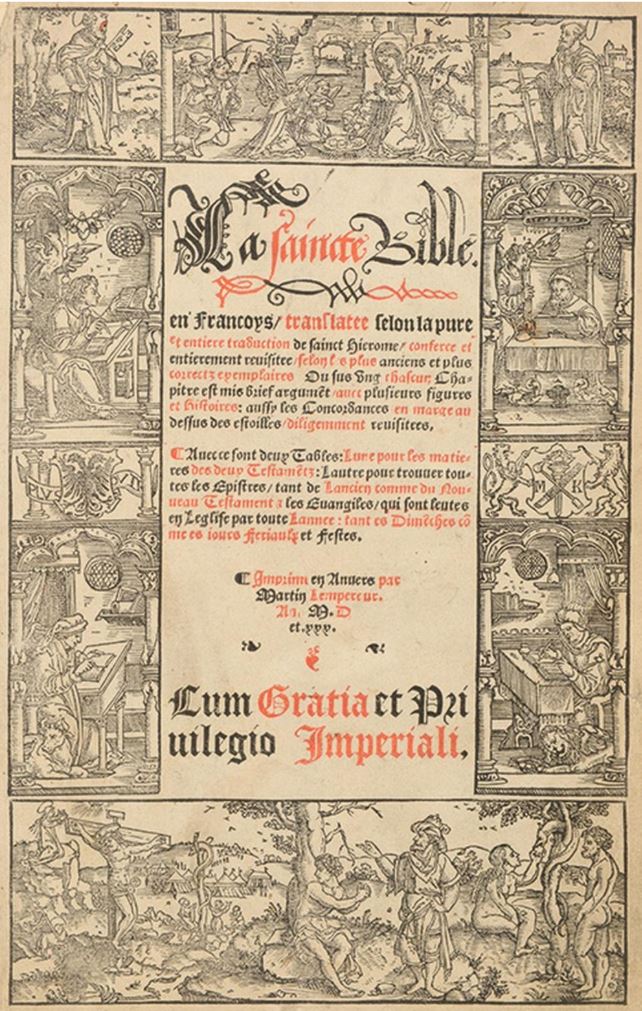

Lefèvre d’Etaples, 1450-1536, undertook the task of translating the New Testament into French; he used the Latin Vulgate as a source text but made some changes in the light of the Greek edition of Erasmus. This translation, published in Paris in 1523 and 1525, was highly successful. Lefèvre’s deep love for God’s Word made him determined to make it accessible to the greatest number of people. To achieve that goal, in June 1523, he published a French translation of the Gospels in two pocket-size volumes. This small format—which cost half the price of a standard edition—made it easier for people with little means to obtain a copy of the Bible. The response of the common people was immediate and enthusiastic. Both men and women were so eager to read Jesus’ words in their mother tongue that the first 1,200 copies printed were out of stock after just a few months.

However, it too received much criticism from the doctors of theology in the University of Paris, the Sorbonne, who, in 1526, called on Parliament to forbid any translation of the Scripture into French. Theologians at the Sorbonne lost no time in going through Lefèvre’s works with a fine-tooth comb. They soon ordered that his translation of the Greek Scriptures be burned publicly, and they denounced some other writings as “favoring the heresy of Luther.” When the theologians summoned him to justify his views, Lefèvre decided to remain “silent” and fled to Strasbourg. There, he discreetly continued translating the Bible. Even though some considered his stance to be lacking courage, he believed that it was the best way to respond to those who had no appreciation for the precious “pearls” of Bible truth. [1]

[1] www.museeprotestant.org/en/notice/humanism-and-translations-of-the-bible-into-the-vernacular/

www.jw.org/en/publications/magazines/watchtower-no6-2016-november/lefevre-detaples-bible-translation/

However, it too received much criticism from the doctors of theology in the University of Paris, the Sorbonne, who, in 1526, called on Parliament to forbid any translation of the Scripture into French. Theologians at the Sorbonne lost no time in going through Lefèvre’s works with a fine-tooth comb. They soon ordered that his translation of the Greek Scriptures be burned publicly, and they denounced some other writings as “favoring the heresy of Luther.” When the theologians summoned him to justify his views, Lefèvre decided to remain “silent” and fled to Strasbourg. There, he discreetly continued translating the Bible. Even though some considered his stance to be lacking courage, he believed that it was the best way to respond to those who had no appreciation for the precious “pearls” of Bible truth. [1]

[1] www.museeprotestant.org/en/notice/humanism-and-translations-of-the-bible-into-the-vernacular/

www.jw.org/en/publications/magazines/watchtower-no6-2016-november/lefevre-detaples-bible-translation/

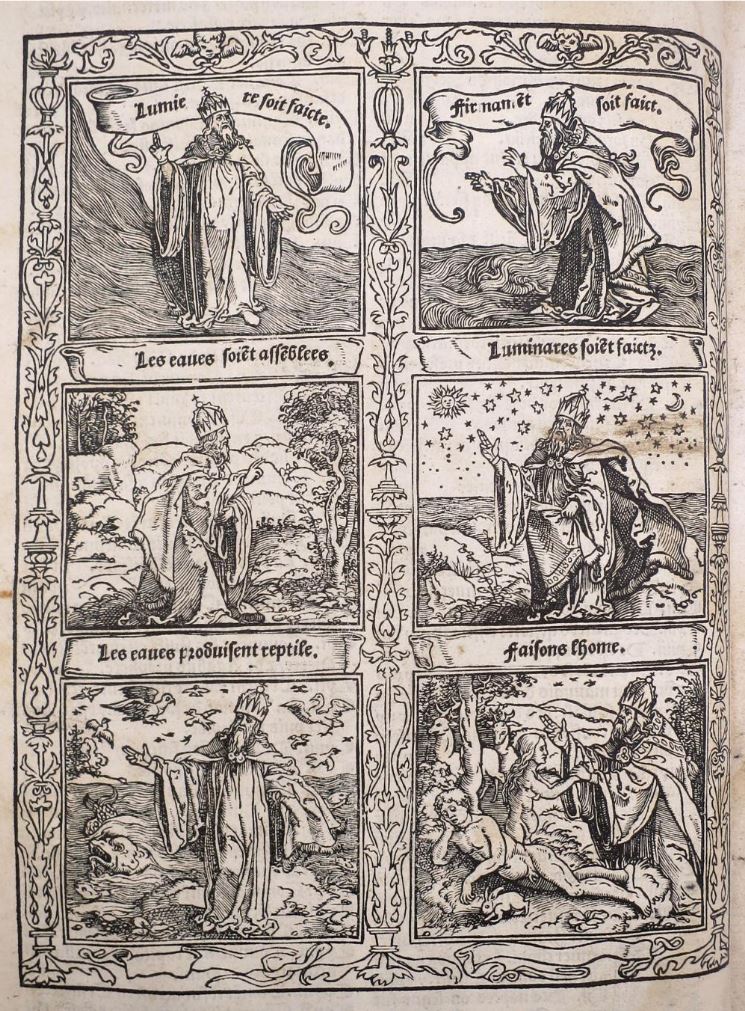

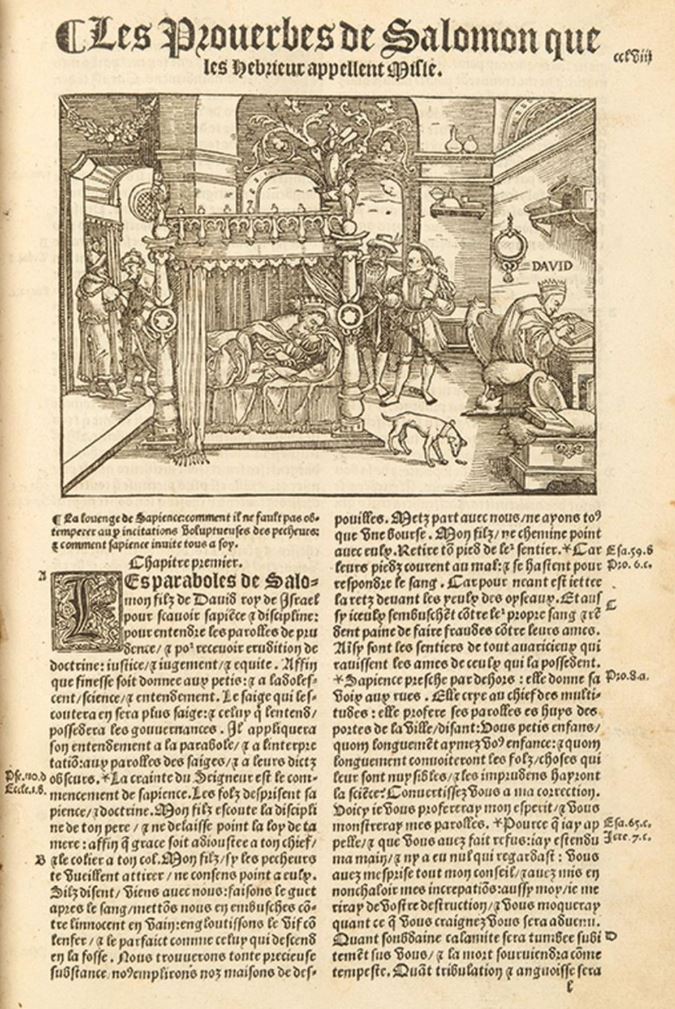

1530 Complete Bible in French by LeFevre

Olivetan Bible

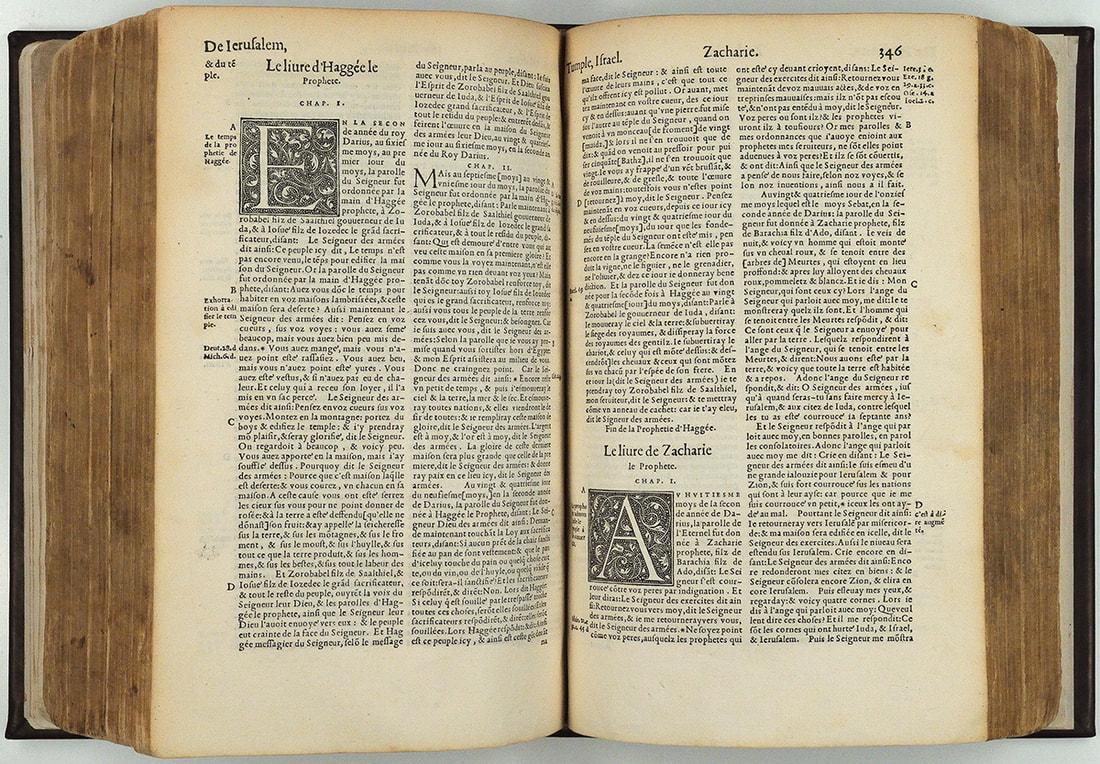

n 1532 at the council of Chanforan, a decision was made to commission a new French translation of the Bible. The Waldesians acknowledged their unity with the Reformation and the protests against the Catholic Church for a faith based Gospel.

Robert Olivetan, 1503-1538, John Calvin’s cousin, at the request of Reformer William Farel and Calvin, was designated to translate the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek, thus, in 1535, publishing the first French translation from the original languages. Olivetan, which means “Midnight Oil,” was a nickname acquired because of his habit of studying late into the night. His real name was Pierre Robert.

Olivétan based his rendering of the New Testament on the French text of Lefèvre d’Étaples, and the Greek text of Erasmus. Olivétan’s choice of vocabulary was often aimed at loosening the grip of Catholicism. For example, he preferred “overseer” to “bishop,” “secret” to “mystery,” and “congregation” to “church.”

In the Hebrew text, Olivétan came across the divine name in the form of the Tetragrammaton thousands of times. He chose to translate it “The Eternal,” an expression that later became common in French Protestant Bibles. In several places, however, he opted for “Jehovah,” notably at Exodus 6:3.

Robert Olivetan, 1503-1538, John Calvin’s cousin, at the request of Reformer William Farel and Calvin, was designated to translate the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek, thus, in 1535, publishing the first French translation from the original languages. Olivetan, which means “Midnight Oil,” was a nickname acquired because of his habit of studying late into the night. His real name was Pierre Robert.

Olivétan based his rendering of the New Testament on the French text of Lefèvre d’Étaples, and the Greek text of Erasmus. Olivétan’s choice of vocabulary was often aimed at loosening the grip of Catholicism. For example, he preferred “overseer” to “bishop,” “secret” to “mystery,” and “congregation” to “church.”

In the Hebrew text, Olivétan came across the divine name in the form of the Tetragrammaton thousands of times. He chose to translate it “The Eternal,” an expression that later became common in French Protestant Bibles. In several places, however, he opted for “Jehovah,” notably at Exodus 6:3.