The Thread of the Truth Remains

owever, even through these Dark Ages, there has always been a remnant of the Gospel shining through. Men who stood against the tyranny of the Church and stood for the Gospel and the Truth. In the beginning, surprisingly, the men who had the greatest impact on Christianity were sent and authorized by the Popes of that time. Even in the Church’s quest for power and wealth, God finds a way to preserve His Word and His people, giving specific meaning to Romans 8:28:

“and in everything, as we know, He co-operates for good with those who love God and are called according to his purpose.”

(Romans 8:28).

(Romans 8:28).

|

The first missionary of significant importance was Patrick, also known as Saint Patrick. The dates of Patrick’s missionary journey to Ireland are in great debate, however, the impact of his journey was substantial. In the latter end of the 5th century, Patrick, commissioned by the Church to go north, brought the Gospel to Ireland. Ireland received this message with enthusiasm, and the old Celtic traditions transformed into Irish Christianity.

Patrick’s influence sparked the light of the Gospel which led to a native of Ireland named Columba, to build a monastery at Durrow in 553. He then proceeded to build an additional 26 more monasteries shortly after. These became a well-known center for education, and at a later period, Durrow and Armagh were called the “Universities of the West”. In 565, Columba founded the monastery of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland. It was in this abbey, Oswald, king of the Northumbrians, was educated, and through his influence, Culdee missionaries were sent to preach among the Saxons. Pope Gregory I sat in the see of the Roman Catholic Church from 590-604. Even though he was head of the corrupted Church, he was a good man, who believed in the Truth of the Bible. He had a love for the Scriptures and believed they should be available to all. He was quoted saying “the Scriptures seem to expand and rise in proportion as to those who read them rise and increase in knowledge. Understood by the most illiterate, they are always new to the most learned. The Scriptures can be compared to a river, in some places, so shallow, that a lamb might easily pass through them; in others so deep, that an elephant might be drowned in them.” In 597, in an attempt to convert the Anglo-Saxons of the north, Pope Gregory sent a group of Roman missionaries, led by a man named Augustine, to introduce Christianity and the Gospel to the north men. These “strangers from Rome” landed on the island of Thanet, and immediately sent word to King Ethelbert, declaring glad tidings of the Gospel.

|

The missionary team bore a silver cross and a painted image of our Savior. The king was hesitant, but willing to hear their message in an open field, lest the strangers should impose upon them their magic. After listening to Augustine’s message, the king answered, “Your words and promises are very fair, but as they are new to us, and of uncertain import, I cannot approve of them so far as to forsake that which I have so long followed with the whole English nation. But because you come from far into my kingdom, and, as I conceive, are desirous to impart to us those things which you believe to be true, and most beneficial, we will not molest you, but give you favorable entertainment, and take care to supply you with your necessary sustenance; nor do we forbid you to preach and gain as many as you can to your religion.”[1]

Thus, the door of the Gospel was opened to Augustine. He brought with him a Latin Bible, probably Jerome’s translation, several hymns, a book of the legends of the Sufferings of the Apostles, an exposition of the Gospels and Epistles, and two more copies of the Gospels. Though this was a Latin Christianity brought to the Anglo-Saxons, it was not a thoroughly Romanized Christianity as in latter times.

Thus, the door of the Gospel was opened to Augustine. He brought with him a Latin Bible, probably Jerome’s translation, several hymns, a book of the legends of the Sufferings of the Apostles, an exposition of the Gospels and Epistles, and two more copies of the Gospels. Though this was a Latin Christianity brought to the Anglo-Saxons, it was not a thoroughly Romanized Christianity as in latter times.

In the year 636, Bishop Aidan, an Irish monk and missionary, founded the monastery of Lindisfarne, off the northeast coast of Northumbria. He brought with him the ecclesiastical doctrine of Iona, Ireland, rather than the corrupted form of Rome. This caused a dispute among the Catholics and Oswy, king of the Northumbrians, determined to call a council at Whitby in 664. There was great debate between the opposing parties, but in the course of this debate, Abott Wilfrith, defender of the Roman faith, quoted Matthew 16:18: “Thou art Peter and upon this rock I will build my Church.” Unfortunately, the king of the Northumbrians was fooled by this popular statement of the Catholics, not knowing that Christ is the Rock and not Peter, therefore, Oswy ignorantly answered that the keys to heaven and hell were granted to the Roman Catholic Church, and not to those who believe in the True Rock, who is Christ. Thus, ended the discussion, and it was determined that Northumbria would conform to the authority and rituals of Rome. How unfortunate this event in Northumbria; the light of the Gospel gaining momentum and then the thief that comes to steal, kill, and destroy, robs the Truth from hungry believers.

Shortly after this "siege" of the Catholic Church, the Light of the Gospel still shown through the darkness by the hand of a diligent Northumbrian monk named bishop Eadfrith. It was this monk who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698AD, transcribed the manuscript of the Gospels in the Latin language sometime around 700AD. This manuscript is known today as the Lindisfarne Gospels. In 793, Vikings from the north attacked and pillaged the monastery, but survivors managed to transport the Gospels safely to Durham, a town on the Northumbrian coast about 75 miles west of its original location.

In the 10th-century, a priest from a small monastery at Durham named Aldred, inscribed a vernacular translation in the Anglo-Saxon tongue between the lines of the Latin text, creating the earliest known Gospels written in a form of English. In an inscription written by Aldred on the Lindisfarne Gospel manuscript informs us that Eadfrith, a bishop of Lindisfarne in 698 who died in 721, created the manuscript to honor God and St. Cuthbert. It is this example in Durham that shows the hunger of those in the North to know the Scriptures in their own language even during a time when the Bible written in any other language than Latin was illegal and a heretical act against the Roman Church.

As the years progressed, the Word of Truth became more suppressed. The see of Rome wanted complete control over the most powerful thing in the world, the Gospel of Jesus Christ. However, there are documented events of people standing for the Word of God, and shining light in the darkness. As we have read above, the north, what we know today as England, Scotland, and Ireland, accepted the Truth of God. We see evidence of their dedication to the Gospel by ancient manuscripts and stories of martyrdom.

An English monk by the name of Venerable Bede, 673-735, was one of those men who brought light to the world through the Word. His most famous work was the “Ecclesiastical History of the English People”, but he also wrote exegetical commentaries on the Scriptures and, what I would consider his most important, the translation of the Latin Vulgate into the Saxon tongue. John Foxe, in his 1563 Acts and Monuments said of Bede and the translated Scriptures,

"Likewise hath it bene in England, as you may finde in the Englysh story called Polycronicon. There it is shewed how when the Saxons did inhabite the land, the king at that time which was a Saxō dyd him selfe translate the Psalter into the language that thē was generally vsed, ye I haue sene a boke at Crowland abbay, which is kept there for a relike. The boke is called S. Guthlakes Psalter. And I wene verely it is a copy of the same, that the kinge did translate, for it is nother English, Laten, Greke, nor Hebrue, nor Douche, but somewhat soundinge to oure English. And as I haue perceiued sith þe time, I was last there, being at Andwarpe the Saxon tounge doth sound likewise after oures, & it is to oures partly agreable. In the same story of Polycronicon is also shewed howe that S. Bede did translate the Euangely of Ihon into English, and the author of the same boke promised that he woulde translate into English all the Bible, ye and perhappes he did so, but I wotte not howe it commeth to passe all such thinges be kept awaye. They maye not come to light, for there are some walking priuely in darknesse, that wil not haue theyr doings knowen, it is no lie that is spoken in the gospel of Ihon." (Foxe, 1563- book 3, page 615)

And in the Prologue to the Wycliffe Bible, Bede is mentioned as having expanded much of the Bible in the Saxon tongue. “For if worldli clerkis loken wel here croniclis and bokis, thei shulden fynde that Bede translatide the Bible and expounide myche in Saxon that was English either comoun langage of this lond in his tyme; and not oneli Bede but also King Alvred.” John Wycliffe, of whom we will dedicate an entire chapter, some 600 years later, used Bede’s commentaries in his personal study.

Shortly after this "siege" of the Catholic Church, the Light of the Gospel still shown through the darkness by the hand of a diligent Northumbrian monk named bishop Eadfrith. It was this monk who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698AD, transcribed the manuscript of the Gospels in the Latin language sometime around 700AD. This manuscript is known today as the Lindisfarne Gospels. In 793, Vikings from the north attacked and pillaged the monastery, but survivors managed to transport the Gospels safely to Durham, a town on the Northumbrian coast about 75 miles west of its original location.

In the 10th-century, a priest from a small monastery at Durham named Aldred, inscribed a vernacular translation in the Anglo-Saxon tongue between the lines of the Latin text, creating the earliest known Gospels written in a form of English. In an inscription written by Aldred on the Lindisfarne Gospel manuscript informs us that Eadfrith, a bishop of Lindisfarne in 698 who died in 721, created the manuscript to honor God and St. Cuthbert. It is this example in Durham that shows the hunger of those in the North to know the Scriptures in their own language even during a time when the Bible written in any other language than Latin was illegal and a heretical act against the Roman Church.

As the years progressed, the Word of Truth became more suppressed. The see of Rome wanted complete control over the most powerful thing in the world, the Gospel of Jesus Christ. However, there are documented events of people standing for the Word of God, and shining light in the darkness. As we have read above, the north, what we know today as England, Scotland, and Ireland, accepted the Truth of God. We see evidence of their dedication to the Gospel by ancient manuscripts and stories of martyrdom.

An English monk by the name of Venerable Bede, 673-735, was one of those men who brought light to the world through the Word. His most famous work was the “Ecclesiastical History of the English People”, but he also wrote exegetical commentaries on the Scriptures and, what I would consider his most important, the translation of the Latin Vulgate into the Saxon tongue. John Foxe, in his 1563 Acts and Monuments said of Bede and the translated Scriptures,

"Likewise hath it bene in England, as you may finde in the Englysh story called Polycronicon. There it is shewed how when the Saxons did inhabite the land, the king at that time which was a Saxō dyd him selfe translate the Psalter into the language that thē was generally vsed, ye I haue sene a boke at Crowland abbay, which is kept there for a relike. The boke is called S. Guthlakes Psalter. And I wene verely it is a copy of the same, that the kinge did translate, for it is nother English, Laten, Greke, nor Hebrue, nor Douche, but somewhat soundinge to oure English. And as I haue perceiued sith þe time, I was last there, being at Andwarpe the Saxon tounge doth sound likewise after oures, & it is to oures partly agreable. In the same story of Polycronicon is also shewed howe that S. Bede did translate the Euangely of Ihon into English, and the author of the same boke promised that he woulde translate into English all the Bible, ye and perhappes he did so, but I wotte not howe it commeth to passe all such thinges be kept awaye. They maye not come to light, for there are some walking priuely in darknesse, that wil not haue theyr doings knowen, it is no lie that is spoken in the gospel of Ihon." (Foxe, 1563- book 3, page 615)

And in the Prologue to the Wycliffe Bible, Bede is mentioned as having expanded much of the Bible in the Saxon tongue. “For if worldli clerkis loken wel here croniclis and bokis, thei shulden fynde that Bede translatide the Bible and expounide myche in Saxon that was English either comoun langage of this lond in his tyme; and not oneli Bede but also King Alvred.” John Wycliffe, of whom we will dedicate an entire chapter, some 600 years later, used Bede’s commentaries in his personal study.

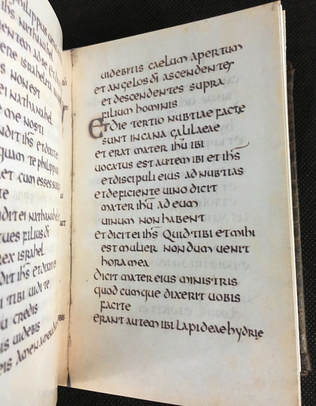

“Stonyhurst Gospel”

8th Century Gospel of John

“Stonyhurst Gospel”

8th Century Gospel of John

The north was unique for the Gospel in that there was evidence of the Word of Truth among the common people. We see this example above from the work of Bede, and we have another example of a small, 8th century Latin Bible of only the book of John. This is significant because it obviously was not a Church bible, for the reason of only being one gospel, but it was also small, measuring only 3.6” x 5.4”. This Bible was someone’s personal Bible they carried with them, proving the devotion and the freedom the north enjoyed. This Bible is known as the “Stonyhurst Gospel” or the “St. Cuthbert Gospel of John”. A facsimile of this Bible is available from AP Manuscripts.

As mentioned in the Wycliff Prologue above, we have another name of significance to carry the Gospel to the world. That is King Alfred of Wessex, 849-899. He was known as a warrior, scholar, and a Christian man who translated the Bible into the vernacular of the people, namely the Saxon tongue. John Wycliffe in the prologue to his Bible states, “King Alvred, that foundide Oxenford, translatide in hise laste daies the bigynning of the Sauter into Saxon, and wolde more if he hadde lyved lengere.” King Alfred brought light again to the pages of English history, and it is no coincidence that he also brought with him the Word of God.

King Alfred’s influence of the Holy Scriptures continued for the next century. The Saxon Church had developed an evangelical spirit, one that clung to the Word of God. King Alfred took the Bible as the foundation of his laws. Not only was the Bible translated into English, but it was also encouraged to read.

At the close of the tenth century, around 975, there lived a Saxon abbot named Aelfric. He continued to translate the Bible into English and preserved the written Word for the common people. He stated,

“I have not labored for the gratification of kings and eldermen, but for the edification of the simple, who know only this Saxon speech. We have therefore put it not into obscure words, but into simple English, that it may easier reach the heart of those who read or hear it.”[2]

These English translations of the Latin Scriptures were still in the pure form of Jerome’s Latin; not yet being corrupted by the impurities and traditions of the Catholic Church. During the Middle Ages, England managed to remove itself from the tyranny of the Holy Roman Empire, but in 1066, the king of Normandy, William the Conqueror, invaded England and took control. This is significant because the influence of the French speaking king would begin to change the Saxon language into the modern English we know today. But it is important to realize that over the 150 years that Normandy ruled England, the Saxon’s didn’t lose their language, it merely improved upon it, shaping it from a barbarous language of peasants, to one day being the common language of the world. This also shows the character and perseverance of the Saxon people. Even though conquered, they were not overrun. If it weren’t for the independence and courage of the Saxon people, the language would have been permanently lost and their religion Roman Catholic.

The thirteenth century began a new era of Saxon literature including new Bible translations into the Saxon tongue. One of distinct importance is a paraphrase of the New Testament Gospels written by a Saxon monk named Ormin. This work, named the Ormulum, was not a translation, but it paraphrased the Gospels from Latin into the English vernacular for the common people. Through the thirteenth, and leading into the fourteenth century, there were other translations of certain sections of Scripture, though they should be considered paraphrases, and not word for word translations, setting the stage for the Wycliffe translation to emerge.

[1] The History of the English Bible by Blackford Condit 1896

[2] The History of the English Bible by Blackford Condit 1896 / Turner’s History of the Ango-Saxons

As mentioned in the Wycliff Prologue above, we have another name of significance to carry the Gospel to the world. That is King Alfred of Wessex, 849-899. He was known as a warrior, scholar, and a Christian man who translated the Bible into the vernacular of the people, namely the Saxon tongue. John Wycliffe in the prologue to his Bible states, “King Alvred, that foundide Oxenford, translatide in hise laste daies the bigynning of the Sauter into Saxon, and wolde more if he hadde lyved lengere.” King Alfred brought light again to the pages of English history, and it is no coincidence that he also brought with him the Word of God.

King Alfred’s influence of the Holy Scriptures continued for the next century. The Saxon Church had developed an evangelical spirit, one that clung to the Word of God. King Alfred took the Bible as the foundation of his laws. Not only was the Bible translated into English, but it was also encouraged to read.

At the close of the tenth century, around 975, there lived a Saxon abbot named Aelfric. He continued to translate the Bible into English and preserved the written Word for the common people. He stated,

“I have not labored for the gratification of kings and eldermen, but for the edification of the simple, who know only this Saxon speech. We have therefore put it not into obscure words, but into simple English, that it may easier reach the heart of those who read or hear it.”[2]

These English translations of the Latin Scriptures were still in the pure form of Jerome’s Latin; not yet being corrupted by the impurities and traditions of the Catholic Church. During the Middle Ages, England managed to remove itself from the tyranny of the Holy Roman Empire, but in 1066, the king of Normandy, William the Conqueror, invaded England and took control. This is significant because the influence of the French speaking king would begin to change the Saxon language into the modern English we know today. But it is important to realize that over the 150 years that Normandy ruled England, the Saxon’s didn’t lose their language, it merely improved upon it, shaping it from a barbarous language of peasants, to one day being the common language of the world. This also shows the character and perseverance of the Saxon people. Even though conquered, they were not overrun. If it weren’t for the independence and courage of the Saxon people, the language would have been permanently lost and their religion Roman Catholic.

The thirteenth century began a new era of Saxon literature including new Bible translations into the Saxon tongue. One of distinct importance is a paraphrase of the New Testament Gospels written by a Saxon monk named Ormin. This work, named the Ormulum, was not a translation, but it paraphrased the Gospels from Latin into the English vernacular for the common people. Through the thirteenth, and leading into the fourteenth century, there were other translations of certain sections of Scripture, though they should be considered paraphrases, and not word for word translations, setting the stage for the Wycliffe translation to emerge.

[1] The History of the English Bible by Blackford Condit 1896

[2] The History of the English Bible by Blackford Condit 1896 / Turner’s History of the Ango-Saxons