Martin Luther

and friend

Philip Melanchthon

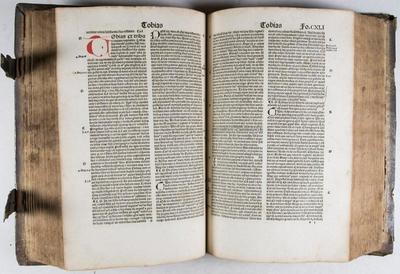

Latin Bible printed at Basel by John Frobenius in 1509

Latin Bible printed at Basel by John Frobenius in 1509

Philip Melanchthon was given the name Philip Schwarzerd at his birth. His father, George Schwarzerd, was a skillful armor maker, producing armor for the princes of the realm. Often, he would refuse payment for his work if he learned his customers were poor. He was a devout Christian, who rose regularly at midnight to offer prayers to God. His wife, and mother of Melanchthon, was named Barbara. She was a good wife and mother, known for her wisdom and German rhymes. Before Melanchthon turned eleven, his father George died. Philip’s grandfather acted as a father to him and his brother. He hired a tutor named John Hungarus, who, as Melanchthon said, “made me a grammarian. He loved me as a son, I loved him as a father, and we will meet, I trust, in eternal life.”

Philip exceled in his studies and understanding. It often happened that travelers would come to visit his grandfather, and young Philip would engage in conversations with them, impressing all those he talked to. Not long after, his grandfather died, and he and his brother were sent to the school of Pforzheim. The boys resided with one of their relatives, the sister of the famous Reuchlin. At Pforzheim, under the tutor of George Simler, Melanchthon progressed rapidly in the learning of science and the study of Greek. Reuchlin often came to Pforzheim and met with young Philip. Amazed at his learning, especially of Greek, Reuchlin gave him a Greek grammar and a Latin Bible, a value of over a year’s wage. The Bible was printed just a short time earlier at Basle by famous printer John Frobenius. It was at this time that Reuchlin changed his name from Schwarzerd to Melanchthon. Both words meant “black earth”, the latter being Greek. It was customary for the learned to change their name into Greek or Latin.

At this time, in 1512, being the age of twelve, he went to the University of Heidelberg. He spent two years there, achieved his Bachelor, and at the age fourteen Reuchlin invited him to Tubingen. This university was well known for its great number of literary men. Here he attended lectures on theology and medicine. He was deeply involved in the study of his Bible. When at the church, between services, he would read his Latin Bible. People were suspicious of this unknown book, being a different size than that of the common prayer book. He always had this Bible with him. Erasmus heard of the upcoming reformer of which he said, “Of Melanchthon I have the highest opinion, and the highest hopes. Jesus grant that this young man may have a long life! He will completely eclipse Erasmus.”

In 1514, at the young age of seventeen, Melanchthon was made a doctor of philosophy and began to teach until 1518, when at this time, the Elector Fredrick, in desiring that his University of Wittemberg would be the most elite in Germany, wanted to fill his halls with professors of ancient languages. Fredrick consulted Reuchlin, who for the Hebrew language there were several suggestions, but for the Greek, there was only one choice, Philip Melanchthon. Philip was twenty-one at this time. Therefore, on 25th day of August 1518, Melanchthon entered upon Wittemberg. The first impression the professors of Wittemberg had of the young teacher was not to their expectations. He was young, and he even appeared younger than he really was. He was of small stature, feeble, and timid. They thought, “is this the man in whom Erasmus and Reuchlin, the greatest men of the age, extol so loudly?” But four days after his arrival, Melanchthon gave his inaugural speech changing the minds of all those in Wittemberg. Luther wrote a letter to Spalatin on the 31st of August saying, “Melanchthon, four days after his arrival, delivered an address so beautiful and so learned, that it was listened to with universal approbation and astonishment. We have soon got the better of the prejudices which his stature and personal appearance had produced. We praise and admire his eloquence; we thank the prince and you for the service you have done us. I ask no other Greek master. But I fear that his delicate body will not be able to digest our food, and that, on account of the smallness of his salary, we shall not keep him long. I hear that the Leipsic folks are already boasting of being able to carry him off from us. Oh, my dear Spalatin, beware of despising his age and personal appearance. He is a man worthy of all honor.”

Melanchthon did however stay in Wittemberg until his death in 1560. Melanchthon began teaching Greek. In his first course, he explained Homer and the Epistle of Titus in the Greek language. Luther again wrote to Spalatin and said, “I recommend to you most particularly the very learned and very amiable Greek, Philip. His class-room is always full. All the theologians in particular attend him. He sets all classes from the highest to the lowest, to the learning of Greek.”

Philip exceled in his studies and understanding. It often happened that travelers would come to visit his grandfather, and young Philip would engage in conversations with them, impressing all those he talked to. Not long after, his grandfather died, and he and his brother were sent to the school of Pforzheim. The boys resided with one of their relatives, the sister of the famous Reuchlin. At Pforzheim, under the tutor of George Simler, Melanchthon progressed rapidly in the learning of science and the study of Greek. Reuchlin often came to Pforzheim and met with young Philip. Amazed at his learning, especially of Greek, Reuchlin gave him a Greek grammar and a Latin Bible, a value of over a year’s wage. The Bible was printed just a short time earlier at Basle by famous printer John Frobenius. It was at this time that Reuchlin changed his name from Schwarzerd to Melanchthon. Both words meant “black earth”, the latter being Greek. It was customary for the learned to change their name into Greek or Latin.

At this time, in 1512, being the age of twelve, he went to the University of Heidelberg. He spent two years there, achieved his Bachelor, and at the age fourteen Reuchlin invited him to Tubingen. This university was well known for its great number of literary men. Here he attended lectures on theology and medicine. He was deeply involved in the study of his Bible. When at the church, between services, he would read his Latin Bible. People were suspicious of this unknown book, being a different size than that of the common prayer book. He always had this Bible with him. Erasmus heard of the upcoming reformer of which he said, “Of Melanchthon I have the highest opinion, and the highest hopes. Jesus grant that this young man may have a long life! He will completely eclipse Erasmus.”

In 1514, at the young age of seventeen, Melanchthon was made a doctor of philosophy and began to teach until 1518, when at this time, the Elector Fredrick, in desiring that his University of Wittemberg would be the most elite in Germany, wanted to fill his halls with professors of ancient languages. Fredrick consulted Reuchlin, who for the Hebrew language there were several suggestions, but for the Greek, there was only one choice, Philip Melanchthon. Philip was twenty-one at this time. Therefore, on 25th day of August 1518, Melanchthon entered upon Wittemberg. The first impression the professors of Wittemberg had of the young teacher was not to their expectations. He was young, and he even appeared younger than he really was. He was of small stature, feeble, and timid. They thought, “is this the man in whom Erasmus and Reuchlin, the greatest men of the age, extol so loudly?” But four days after his arrival, Melanchthon gave his inaugural speech changing the minds of all those in Wittemberg. Luther wrote a letter to Spalatin on the 31st of August saying, “Melanchthon, four days after his arrival, delivered an address so beautiful and so learned, that it was listened to with universal approbation and astonishment. We have soon got the better of the prejudices which his stature and personal appearance had produced. We praise and admire his eloquence; we thank the prince and you for the service you have done us. I ask no other Greek master. But I fear that his delicate body will not be able to digest our food, and that, on account of the smallness of his salary, we shall not keep him long. I hear that the Leipsic folks are already boasting of being able to carry him off from us. Oh, my dear Spalatin, beware of despising his age and personal appearance. He is a man worthy of all honor.”

Melanchthon did however stay in Wittemberg until his death in 1560. Melanchthon began teaching Greek. In his first course, he explained Homer and the Epistle of Titus in the Greek language. Luther again wrote to Spalatin and said, “I recommend to you most particularly the very learned and very amiable Greek, Philip. His class-room is always full. All the theologians in particular attend him. He sets all classes from the highest to the lowest, to the learning of Greek.”

Luther and Melanchthon together at work

Luther and Melanchthon together at work

Luther and Melanchthon soon became good friends. Melanchthon said of Luther, “If there is any one whom I love strongly, and whom my whole soul embraces, it is Martin Luther.” The two made each other stronger, creating a bond, united by the hand of God, in the progress of the Reformation. Luther animated Melanchthon; Melanchthon moderated Luther. Luther taught Philip his theology of the Word of God, while Melanchthon taught Luther a deeper understanding of Greek. Often did the meaning of a Greek word expounded by Melanchthon shed light on Luther’s theological views. Martin Luther, before meeting this Greek scholar, having studied Greek himself, attempted to translate the New Testament into German, but these attempts were not successful until he met Melanchthon. The impulse which Melanchthon gave to Luther, in regard to the translation of the Bible, is one of the most remarkable circumstances in the friendship of these two great men. It would be four years later, in 1522, that the world would see the first translation of the Greek New Testament translated into the common tongue.