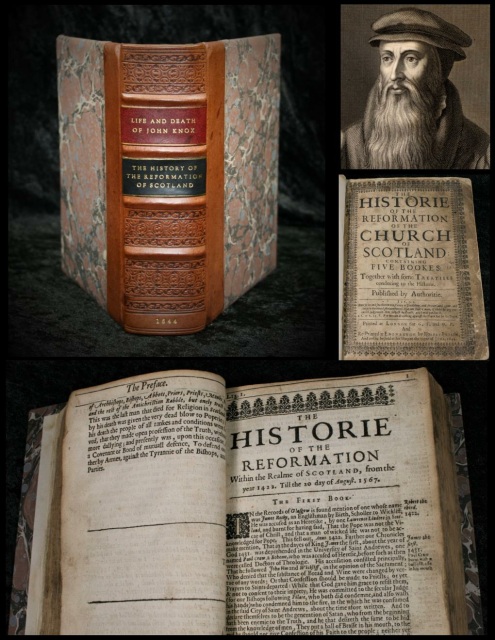

1644 History of the Sottish Reformation and the Life and Death of John Knox- $975 SOLD

SKU:

$975.00

$975.00

Unavailable

per item

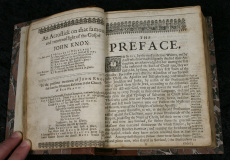

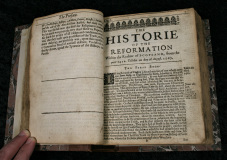

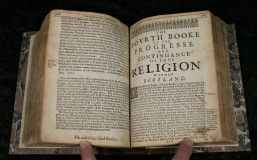

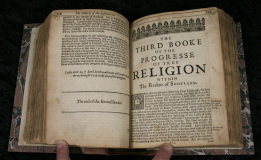

1644 History of the Scottish Reformation

and the Life and Death of John Knox

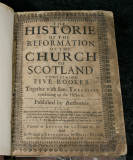

Printed by Robert Bryson, London 1644

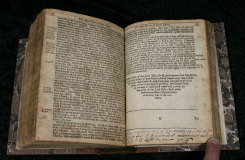

Quarto 8” x 6” x 2-1/2”

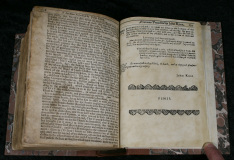

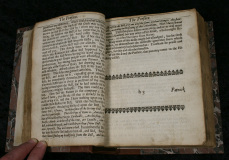

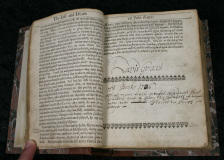

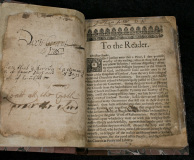

Condition Report: Newly rebound by Starr Bookworks. Some browning and foxing throughout. First pages of book have been repaired. Binding secure and sound. Last page of the Sermon of John Knox supplied in facsimile.

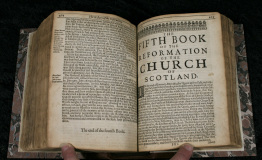

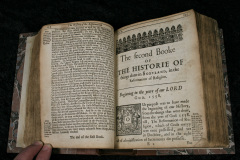

This book contains the following volumes of work:

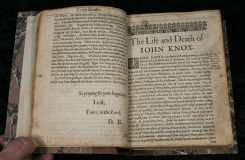

- The Life and Death of John Knox

- Five Books on the History of the Reformation in Scotland

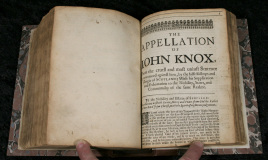

- The Appellation of John Knox

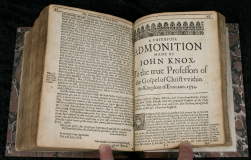

- A Faithful Admonition Made by John Knox

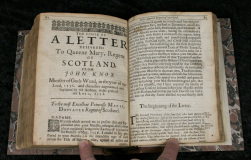

- A Letter Delivered to Queen Mary from John Knox

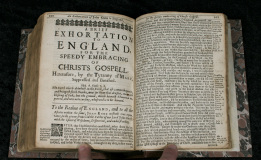

- An Exhortation of John Knox to England

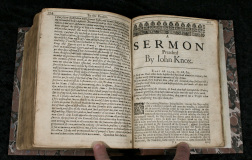

- A Sermon Preached by John Knox

Sold out

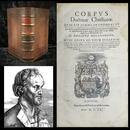

1560 Corpus Doctrinae Christianae

Philipp Melanchthon, First Edition

$6,500

Philipp Melanchthon, First Edition

$6,500

The History of John Knox

Capture and Release

After the Protestant George Wishart’s martyrdom in St. Andrews, Knox came to the town with some of his young students and, in 1547, joined the group of Reformers living in the castle there. When Knox was appointed to preach, he refused, but he was virtually manhandled into accepting a call from the castle congregation to become their minister. Within a matter of months, however, the castle was under siege from French ships in St. Andrews Bay. Knox and others were captured, and he became a galley slave for the next year and a half.

In 1549, Knox was released and made his way to England. He pastored a congregation at Berwick, but soon he moved to Newcastle. He then became a royal chaplain during the days of the young King Edward VI. The death of Edward in 1553 was a body blow to the reforming party in England, leading as it did to the enthronement of Mary Tudor (“that idolatrous Jezebel” were Knox’s carefully chosen words to describe her). Knox sought refuge on the Continent.

Life on the Continent

Between 1553 and 1559, Knox lived a somewhat nomadic existence. He spent some time with Calvin in Geneva, calling it “the most perfect school of Christ . . . since the days of the apostles.” Thereafter, he accepted a call to pastor the English-speaking congregation at Frankfurt am Main.

Knox married Englishwoman Marjorie Bowes and, in 1556, returned to Geneva, where he pastored a congregation of some two hundred refugees. The following year, he received an urgent invitation to come back to Scotland — 1558 was the scheduled time for the marriage of the young Mary, Queen of Scots, to the dauphin of France, an event that seemed to destine Scotland for permanent Roman Catholic rule.

A taste of Knox’s vigor can be savored in a letter he wrote that same year to the people of Scotland, urging them not to compromise the gospel. He reminded them that they must answer for their actions before the judgment seat of God:

Return to Scotland

In 1559, Knox finally returned home to begin his most important phase of public ministry as the champion of the kirk (the Scottish term for church). Despite his lengthy absences from his native land, several things equipped Knox to lead the Reformation there: his name was associated with the heroes of the recent past, his sufferings authenticated his commitment, his broad experience had prepared him for leadership, and his sense of call made him “fear the face of no man.” So, for the next thirteen years, Knox gave himself to the reformation of Scotland.

By the summer of 1572, Knox was a shadow of his former self, and by November, it was clear he was not long for this world. On the morning of November 24, he asked his second wife, Margaret, to read 1 Corinthians 15 to him, and around five o’clock came his final request: “Read where I cast my first anchor” (presumably in faith). She read John 17. By the end of the evening, he was gone.

Many explanations have been forthcoming for Knox’s influence and that of the Scottish Reformation. No doubt there were many factors at work in the providence of God that brought about such spiritual renewal. But Knox’s own conviction was this: “God gave His Holy Spirit to simple men in great abundance.” Therein lies the greatest lesson of his life.

Article by Sinclair Ferguson, Desiring God.org

After the Protestant George Wishart’s martyrdom in St. Andrews, Knox came to the town with some of his young students and, in 1547, joined the group of Reformers living in the castle there. When Knox was appointed to preach, he refused, but he was virtually manhandled into accepting a call from the castle congregation to become their minister. Within a matter of months, however, the castle was under siege from French ships in St. Andrews Bay. Knox and others were captured, and he became a galley slave for the next year and a half.

In 1549, Knox was released and made his way to England. He pastored a congregation at Berwick, but soon he moved to Newcastle. He then became a royal chaplain during the days of the young King Edward VI. The death of Edward in 1553 was a body blow to the reforming party in England, leading as it did to the enthronement of Mary Tudor (“that idolatrous Jezebel” were Knox’s carefully chosen words to describe her). Knox sought refuge on the Continent.

Life on the Continent

Between 1553 and 1559, Knox lived a somewhat nomadic existence. He spent some time with Calvin in Geneva, calling it “the most perfect school of Christ . . . since the days of the apostles.” Thereafter, he accepted a call to pastor the English-speaking congregation at Frankfurt am Main.

Knox married Englishwoman Marjorie Bowes and, in 1556, returned to Geneva, where he pastored a congregation of some two hundred refugees. The following year, he received an urgent invitation to come back to Scotland — 1558 was the scheduled time for the marriage of the young Mary, Queen of Scots, to the dauphin of France, an event that seemed to destine Scotland for permanent Roman Catholic rule.

A taste of Knox’s vigor can be savored in a letter he wrote that same year to the people of Scotland, urging them not to compromise the gospel. He reminded them that they must answer for their actions before the judgment seat of God:

Return to Scotland

In 1559, Knox finally returned home to begin his most important phase of public ministry as the champion of the kirk (the Scottish term for church). Despite his lengthy absences from his native land, several things equipped Knox to lead the Reformation there: his name was associated with the heroes of the recent past, his sufferings authenticated his commitment, his broad experience had prepared him for leadership, and his sense of call made him “fear the face of no man.” So, for the next thirteen years, Knox gave himself to the reformation of Scotland.

By the summer of 1572, Knox was a shadow of his former self, and by November, it was clear he was not long for this world. On the morning of November 24, he asked his second wife, Margaret, to read 1 Corinthians 15 to him, and around five o’clock came his final request: “Read where I cast my first anchor” (presumably in faith). She read John 17. By the end of the evening, he was gone.

Many explanations have been forthcoming for Knox’s influence and that of the Scottish Reformation. No doubt there were many factors at work in the providence of God that brought about such spiritual renewal. But Knox’s own conviction was this: “God gave His Holy Spirit to simple men in great abundance.” Therein lies the greatest lesson of his life.

Article by Sinclair Ferguson, Desiring God.org